Erik Freeland/Corbis via Getty Images

“Michael jumps to conclusions. I can’t be friends w/ Tom, just because I talk to him, it doesn’t mean I like him. I really have to stop going over there.”

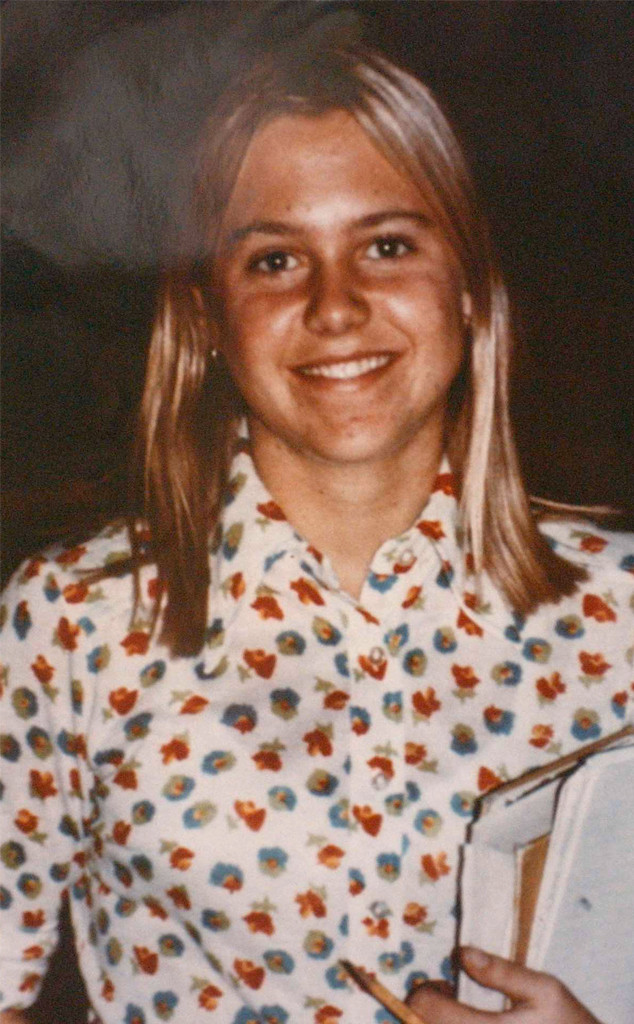

So 15-year-old Martha Moxley wrote in her diary in September of 1975, referring to Michael and Thomas Skakel, brothers who lived next door in Greenwich, Conn., a posh town whose name remains synonymous with money and privilege.

A little over a month later, Moxley was dead, smashed over the head and stabbed with a golf club in the driveway of her family’s home and dumped next to a tree in the backyard, where she was found by a friend the next morning. It was the first murder in Greenwich in 30 years.

Michael and Tommy were questioned, as was their new live-in tutor, Kenneth Littleton.

And then the case went cold for 23 years.

But in 1998, a one-man grand jury started reviewing all the evidence in the Moxley case. Eighteen months later, on Jan. 18, 2000, an arrest warrant was issued for an unnamed juvenile.

The suspect in question turned out to be Michael Skakel, who, like Martha, was 15 in 1975. He was 39 years old when he turned himself in on Jan. 19 and was charged with Martha’s murder.

“Michael is one of the most honest and open people I know,” cousin Douglas Kennedy, one of Robert F. Kennedy‘s 11 children, told People a few weeks later. “He cares about people more than anybody I’ve ever met, and there is no possible way he’s involved in this.”

Despite a lack of physical evidence linking him to the crime, prosecutors put Skakel in the vicinity and painted a compelling picture of a troubled rich kid with connections who lost his temper and savagely beat his beautiful neighbor to death and then later told people in rehab that he had done it.

But then, after spending 11 years in prison, Skakel was released on bail after his conviction was vacated. As it stands, he remains free on bail, once again innocent until proven guilty in the eyes of the law, as if he’d never gone on trial.

“I’m sure that Michael Skakel is the one that swung the golf club,” Dorthy Moxley told the Greenwich Sentinel in 2015. “In my mind he’s still a murderer, running around out there.”

Skakel is one of seven children born to Rushton Skakel, the hard-drinking son of a carbon manufacturing magnate, and Anne Skakel (née Reynolds), who died of brain cancer in 1973 when she was 41.

Rushton’s younger sister Ethel had married Bobby Kennedy, a consuming family tie that would prove as heavy as a chain when it came to the rabid media coverage of the Moxley murder trial but which would also provide Michael with a prominent corner of unflagging support.

By all accounts, including his own, young Michael had a tumultuous relationship with his father, who could be domineering and neglectful, particularly after Anne died.

Martha’s mother, Dorthy Moxley, later said that she didn’t even know until reading some of her late daughter’s diary that Martha was that friendly with the Skakel brothers, particularly Tommy, who, the girl wrote, had put his arm around her in the car and otherwise seemed to show interest, while Michael flirted with her friend Jackie.

The Moxleys—Dorthy, accountant husband David Moxley and their kids, Martha and her older brother John—had moved to the Greenwich neighborhood of Belle Haven from the Bay Area city of Piedmont, Calif., in early 1974.

“It was one of these neighborhoods, the kids could just go meet people… very safe,” Dorthy recalled to former prosecutor Laura Coates in the Oxygen series Murder and Justice: The Case of Martha Moxley, episode two of which airs tonight. “Everyone liked everyone, it seemed like.”

Martha was voted “Best Personality” in middle school, got straight As and played basketball. Her braces had recently come off and she was smiling brightly in every picture. She was supposed to be grounded because of some minor infraction the previous weekend, but Oct. 30, 1975, was “Mischief Night,” and her mother relented when she wanted to go out.

“It was cold, very cold,” Dorthy recalled to the Greenwich Sentinel 40 years later. “Martha was going to wear her shearling lamb jacket. She just loved it. She’d just gotten it, her shearling lamb jacket. But she thought, ‘No, there’s going to be mischief, so I think I’d better wear my old down parka.’ So she went out in her old blue down parka.”

When Martha still wasn’t home by around 2 a.m., Dorthy called the house of her daughter’s friend Sheila McGuire, whose mom woke her up to ask if she’d seen Martha that night. She hadn’t. Dorthy called the police at 3:45 a.m. and again rang the McGuires at 4 a.m., but Sheila still wasn’t too concerned. It was Mischief Night after all.

Dorthy eventually fell asleep but woke up to Martha’s empty room. She called Helen Ix, who said the last she knew was that Martha had been hanging out with Tommy Skakel the previous night. Martha was last seen alive leaving the Skakel house, where kids tended to congregate because there wasn’t much adult supervision.

When Dorthy went next door to look for Martha, Michael opened the door. He didn’t know where Martha was, he said. Dorthy, motioning to the big camper parked outside, asked if it was possible that Martha had passed out in there. Michael took Dorthy to look, but the camper was empty.

Sheila McGuire was the one who found Martha shortly after noon on Halloween while walking through the neighborhood looking for her.

There was a piece of the metal shaft of a golf club sticking out of her neck, while another piece of the club—a six-iron—lying nearby. She had been hit repeatedly in the head, so hard that the club apparently broke. Her jeans and underwear were pulled down around her ankles, but investigators wouldn’t find direct evidence of sexual assault.

Despite being hysterical, Sheila, when she ran to front of the Moxley house to tell Dorthy, at first said that they needed to call 911, that Martha had been attacked but surely would be fine. Jean Walker, one of Dorthy’s friends who had been inside having coffee with her, assuring her that Martha would turn up, went outside to look.

“Is she dead?” Dorthy asked. “I think so,” Jean replied.

Pool Photo/Getty Images

Police matched the golf club to a set that had belonged to Anne Skakel but was since passed down to daughter Julie. Tommy, who was initially the focus of the investigation because he was the last person to see Martha, told detectives he had briefly flirted with her outside and last saw her walking toward her house—150 yards away from his own—at around 9:30 p.m. on Oct. 30. Then, he said, he watched some of The French Connection with Kenneth Littleton and went to his room to work on a report for school.

Michael said he was at a cousins’s house during the window in which they determined the murder had been committed, between 9:30 and 10:15 p.m.

Kenneth Littleton, who had just moved in with the family that day, was also initially considered a person of interest. The 24-year-old told police he was in watching The French Connection the whole time. (He left the Skakels’ employ eight months later. In 1977, he pleaded guilty to a burglary charge in his native Massachusetts and was sentenced to five years of probation.)

According to Timothy Dumas‘ 1998 book Greentown, Stephen Skakel, who was 9 at the time, told his friend Lucy Tart on the school bus the next morning (before Martha’s body was found) that he had been awakened in the middle of the night by screams. Lucy told her mother, who told police, who reached out to Rush Skakel, who said he’d talk to Stephen. After that, the story police heard was that Stephen had actually been woken up by Martha’s laughter as she was leaving.

Numerous people also heard dogs barking that night, from near the Moxley home all the way down to Long Island Sound, 600 yards away.

A security guard (the well-heeled enclave was rife with private security) had provided a description of a man who he had seen slip between two houses across the street from the Skakels’ place at around 10 p.m. the night of the murder.

According to Dumas, police questioned 26-year-old Dan Connor, who resembled the description, on Nov. 3, 1975, but he had been at a friend’s house (also watching The French Connection) when the murder took place. Asked who he thought might be responsible, Connor mentioned that the Skakels took pills, so maybe Tommy had flown off the handle. Years later Connor told Dumas that he’d “be shocked if either [Michael or Tommy] had anything to do with that murder.”

Police also talked to Martha’s boyfriend Peter Ziluca, who she’d been planning to go to the Green Leaf Dance with two weeks later. He had last seen her Oct. 30 in the student center at Greenwich Academy, where they talked about their Halloween plans. Home that night, Peter’s mother asked if he wanted to take the car to go to Martha’s, but he didn’t have a license, and had smoked some pot earlier in the day and remembered feeling freaked out by the dark and the wind. So he stayed in, watching The French Connection (there were only three TV networks, plus PBS, then), and fell asleep.

“I mean, if only I’d gotten in the car that night and illegally driven down to Belle Haven,” Ziluca told Dumas. “Maybe Martha wouldn’t be dead. Or maybe I’d be dead, too.”

Detectives gave Peter a polygraph test in 1975, as they did with dozens of others, and he was crossed off the list. Remaining on the list, was Tommy Skakel.

On Jan. 22, 1976, Rushton Skakel stopped giving investigators access to his family.

Rush told David and Dorthy Moxley in March 1976 that Tommy had undergone a battery of psychiatric tests and that, without going into further detail, the results indicated that the boy couldn’t have killed Martha.

Thomas Keegan, then the police chief in Greenwich, would later testify at Michael’s trial that he had filed a request for an arrest warrant for Thomas in 1976 but was denied by then-State’s Attorney Donald Browne, who didn’t think there was probable cause.

The Moxleys—who had remained friendly with their neighbors until they shut down the investigation—eventually moved away.

Dorthy, David and John Moxley moved to Manhattan, then to Annapolis, Md., in 1986. David died of a heart attack at 57 in 1988. “I think the fact that he kept everything inside added to his early demise,” Dorthy told People.

“It’s been 43 years and it’s one of those things where different times you feel different ways,” John Moxley told Laura Coates recently as they drove through Belle Haven on The Case of Martha Moxley. “You just can’t help but wonder what might have been, if [Martha] had been allowed to live her life out. Would she have been the CEO of a major corporation or the president of the Peace Corps? I made a lot of effort over the years not to go down that dark road I couldn’t get out of.”

The twists and turns in the case over the past 28 years, let alone the last 43, have kept the Moxleys and the Skakels on edge, but it was those who stayed the course, and who picked up the trail when it seemingly had grown cold, that ultimately led to what the Moxleys believed was the right outcome after decades of feeling that whoever killed Martha had gotten away with it. Of course, the same can be said for those who carried the torch in the quest to set Michael Skakel free.

Pool Photo/Getty Images

Skakel, who started drinking heavily at 13 after his mother died, was arrested for drunk driving in 1978, after which he was sent to the Élan School in Poland, Maine, a private school for kids with behavioral and substance abuse problems (and, for the most part, wealthy families).

He ran away from Élan a couple of times and was in and out of rehab before getting sober. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a vigilant defender of Michael’s innocence, credited his cousin for helping him quite drinking as well in 1983. Michael competed on the international speed skiing circuit, married golfer Margot Sheridan and graduated from Curry College, where he found help for the dyslexia that had plagued him all his life, in 1993. He and Margot had a son in 1998 and they settled in tony Hobe Sound, Fla.

Skakel was close to a number of his Kennedy cousins, but according to him, a rift opened up when, after working briefly for Michael Kennedy (one of RFK’s 11) at Citizens Energy Corp, he was questioned by the FBI about an alleged affair his cousin was having with an underage babysitter. Skakel told the Feds what he knew and the Kennedys were mortified.

“I am a member of a family sick unto death with generations of secrets,” Skakel wrote in a 1997 proposal for a tell-all book about his family, to be called Dead Man Talking: A Kennedy Cousin Comes Clean.

But in 1991, a sexual assault charge against William Kennedy Smith (son of Bobby Kennedy’s sister Jean Kennedy Smith) led to a claim—told to journalist Dominick Dunne, whose specialty was the goings-on and moral failings of high society—that Smith might have been at the Skakel house the night of Moxley’s murder. The tip proved unfounded, and Smith was acquitted of sexual battery. But Dunne’s interest in the case was re-piqued and he ended up contacting Dorthy Moxley to check in on what came of the investigation; the unsolved crime was the basis for his 1993 novel A Season in Purgatory.

At first Don Browne, who had pumped the brakes on going after Tommy in the 1970s, said it was too late for an investigative grand jury. In the wake of the Smith rumor, however, the New York Post ran a story that noted how the local Greenwich Time and Stamford Advocate papers had recruited Newsday reporter Leonard Levitt to do a deep dive on the Moxley case back in 1982 and then refused to publish his story. Soon after the Post story came out, they ran the decade-old piece.

All things considered, Browne ordered a full re-investigation.

“It’s in the past, and that’s it,” Tom Skakel told the Associated Press when contacted for his thoughts on the matter in September 1991. “I just want to leave it there. I have my own life. It’s private.”

With the case reopened, Rushton Skakel hired a private investigation firm, Sutton Associates, to clear his family’s name once and for all.

Instead, in what became known as the Sutton Report, Tom told one of the investigators that he and Martha had fooled around (as opposed to just flirted) before they parted ways that night at around 10 p.m., while Michael—who had said in 1975 that he was away at a cousin’s house watching an episode of Monty Python, then came home at 11:30 p.m. and went to bed—said that he, upon drunkenly returning to the neighborhood that night, had climbed a tree and masturbated outside Moxley’s bedroom window. Climbing down, he heard voices and ran home, he recalled.

A copy of the Sutton Report fell into Dominick Dunne’s hands, and the author later said that he provided a copy to State Inspector Frank Garr, who had originally worked the case as a detective.

When Garr found out in 1995 that Michael Skakel had apparently lied to detectives 20 years beforehand, Garr—who had previously had his eye on Michael (unlike Dunne, who liked Tommy for the murder)—took it upon himself as well to get Martha’s murder solved once and for all.

“In fact, he started talking about Michael in the early 1990s and I didn’t even believe him,” Levitt, whose book about the case, Conviction, came out in 2003, told Greenwich Time.

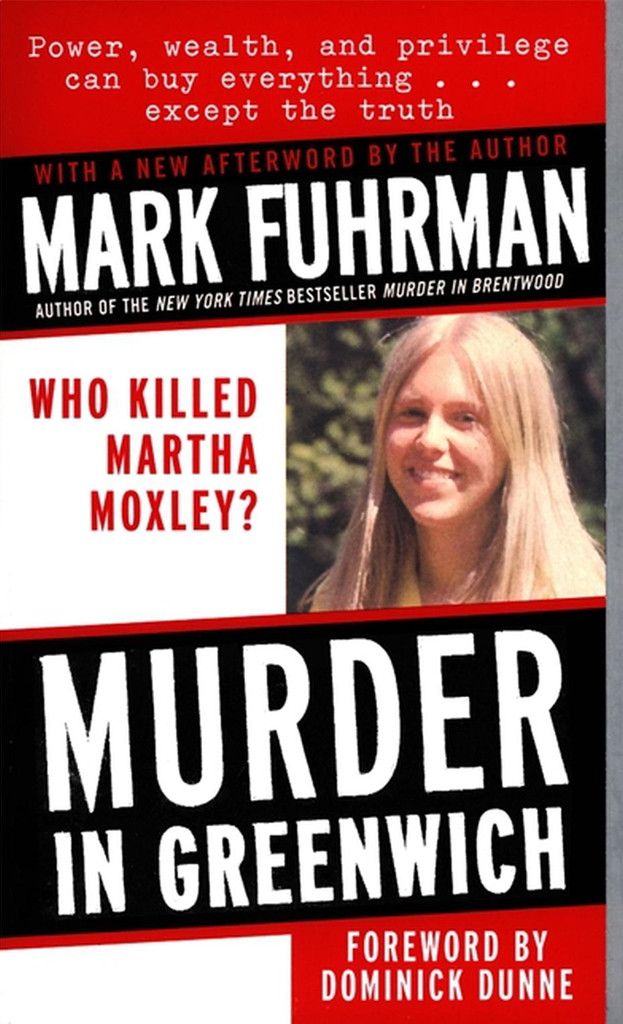

And because it’s a small world after all, Mark Fuhrman, who in 1995 resigned from the LAPD after old recordings of him using racist language surfaced during the O.J. Simpson murder trial, was given a copy of the Sutton Report and he concluded—as detailed in his 1998 book Murder in Greenwich—that Michael, not Tommy, killed Martha.

“Michael Skakel puts himself at the crime scene, and Michael Skakel makes admissions that only a murderer would make,” Fuhrman later told 48 Hours.

And his wasn’t the only familiar name who factored into both infamous cases: forensics specialist Dr. Henry Lee, a defense witness for Simpson, testified for the prosecution in the Moxley case, having joined the investigative team when the case was reopened in 1991. Dominick Dunne, too, famously covered the Simpson and Skakel trials for Vanity Fair—and it was Dunne who gave Fuhrman the Sutton Report. He wasn’t a huge fan of the ex-cop, but they shared similar opinions of O.J. Simpson.

In June 1998, Don Browne’s successor, Jonathon Benedict, called for a special grand jury to convene.

“I’ve been going around pinching myself to see if it’s really happening,” Dorthy Moxley told Dumas.

And so, a one-man grand jury, Superior Court Judge George Thim, called more than four dozen witnesses, including Kenneth Littleton, who was granted immunity in exchange for his testimony, and several people who claimed that Michael had talked to them about the murder at Élan.

“The first words he ever said to me was, ‘I’m going to get away with murder. I’m a Kennedy,'” former Élan student Greg Coleman told the grand jury. “He made advances to her, and she rejected his advance. He drove her skull in with a golf club.”

Thim finished up in December 1999. A few weeks later, Michael Skakel was arrested.

“You’ve got the wrong guy,” Michael told Dorthy Moxel at his arraignment in March 2000, where he pleaded not guilty.

TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images

Dorthy had purposely kept herself ignorant of the case’s grislier details for years as a way of protecting herself, but she stoically sat through the autopsy photos, the graphic testimony and all other details amounting to a mother’s worst nightmare at trial.

Lacking forensics tying Skakel to the crime scene, the prosecution pegged its case to the witnesses who said that Michael had basically confessed to them, despite some issues with their stories. The trial began in May 2002.

Greg Coleman, who had told the grand jury that Michael had said five or six times at school that he had killed Martha, testified at a subsequent preliminary hearing that it was once or twice. Asked why he changed his story, he admitted to being on heroin in front of the grand jury. Coleman died of a heroin overdose in August 2001, but his previous testimony was played in court.

Greg’s widow, Elizabeth Coleman, was later called to corroborate her late husband’s testimony, saying that Greg had told her about knowing Skakel at school and that Michael “told him he had murdered her with a golf club” and would get away with it because “he was related to the Kennedys.” Another former student, Jennifer Pease, also testified that Greg told her something similar.

Élan alum John Higgins testified that he heard Michael launch into a teary monologue about that night that ended in him saying, “I did it.”

”He related that he later was in his garage and he was running through some woods,” Higgins said. “He had a golf club in his hands. He looked up, he saw pine trees. The next thing that he remembers is that he woke up in his house, and that’s the story that he related to me.” Skakel was crying and saying he didn’t know whether he did it or not, Higgins continued. “He thought he may have done it. He didn’t know what happened. Eventually he came to the point that he did do it. He must have done it. ‘I did it.'”

Higgins acknowledged under cross-examination that he really didn’t know if Skakel was guilty or not.

Two other former students, Charles Seigan and Dorothy Rogers, testified that they never heard Michael confess, although he was taunted by classmates about the crime during their group therapy sessions.

”He never admitted it,” Seigan said. ”He never denied it.”

Classmate Elizabeth Arnold testified about what she heard from Michael in group therapy as well. “He didn’t know what happened that night,” she said. ”He was very drunk and he was in a blackout. And he didn’t know if he had done it or if his brother had done it.”

Arnold also said that Michael had inferred that his brother “stole his girlfriend”—a jealous rage being the motive prosecutors were arguing. “And I said,” Arnold continued, “how could something like that have happened? How could your brother have done that to you? And he said, well, they didn’t really have sex, but they were fooling around. He stole his girlfriend.”

Under cross, Arnold said that she didn’t mention the stolen girlfriend to the grand jury because she hadn’t remembered it at the time. She acknowledged that since testifying the first time, she had read Fuhrman’s Murder in Greenwich, which made the case for Michael’s guilt.

Next up, per the New York Times, Élan student turned staffer Alice Dunn testified that she never heard Michael confess, that he said he couldn’t remember, and that it was possible either he or Tommy was responsible.

“He continually denied,” Dunn said. ”He never said the words, I did it. He said, ‘I didn’t do it,’ which became, ‘I don’t know.'”

Michael Meredith, who met Skakel in 1987 while working on Bobby Kennedy’s eldest son Joe Kennedy’s congressional campaign, testified that Skakel had told him about climbing a tree and masturbating that night outside Martha’s window.

About the killing, “Michael instigated the conversation,” Meredith recalled. “He said, ‘I want you to know, I’m innocent of that.'”

Meredith also said that, after that day, he didn’t want to have anything more to do with Skakel, because of “the fear factor. I felt that Michael Skakel had violence boiling under the skin.”

Childhood friend Andrew Pugh then testified that Skakel had told him that he “liked Martha quite a bit and had a crush on her,” but Martha “didn’t seem as interested. She seemed to be not quite as enthusiastic.” Michael and Tommy had a “competitive, contentious” relationship, Pugh said.

He and Skakel lost touch after 1977, Pugh continued, but in 1991 they ran into each other and Skakel wanted to rekindle the friendship. “I expressed some reservations,” Pugh testified. “I asked him if he was involved in [Martha’s] murder. He said ‘No, I wasn’t. But a strange thing happened. I was up in the tree that night masturbating.'”

As part of his 1997 book proposal, Michael had recorded some audio tapes, in one of which he said about the night of Martha’s murder, “I ran home and I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, I hope to God no one saw me jerking off’…and I remember thinking ‘Oh, my God, if I tell anyone I was out that night, they’re gonna say I did it.'”

Julie Skakel, Michael’s sister, testified about seeing someone dart through their yard at around 9:30 p.m.—when Michael had said he was over at his cousin’s house—and, though she told police back in 1975 (and the grand jury in 1998) that she thought it was her brother Michael, she no longer could be sure. A lot of kids were out running around that night, she said.

Rush Sr. and all of the Skakel siblings attended the trial at one point or another, including Tommy, who lived in Massachusetts and reportedly hadn’t been in the same room with Michael in decades.

“I think they love each other, but they’re not close, as many siblings aren’t,” longtime Skakel family attorney Emanuel Margolis told the Hartford Courant at the time. “They’re leading very different lives, but I have no doubt they love each other.”

Catrina Genovese/Getty Images

Dorthy Moxley told the Hartford Courant while the jury was deliberating that the progress in the case “happened gradually, so I had some years to get used to everything. It sort of gave me a job to do. There were a lot of little steps leading to this trial, so by the time it occurred, I was not overwhelmed. When you first lose someone, it’s like new mountains, all sharp and pointy. But over time, that pain wears away, like old mountains that are rounded and smooth and soft green.”

The trial lasted a month and, after three days of deliberations, Skakel was found guilty on June 7, 2002. That August he was sentenced to 20 years to life in prison.

“Today is a day where there is a winner and a loser,” Dorthy Moxley told reporters after the verdict. “I just hate those days… I wanted to find justice for Martha. That’s what this is. It’s all about Martha. I have empathy for the Skakel family.”

Brother David Skakel said in a statement on the family’s behalf, “For our family, grieving has coincided with accusations. For our entire family, the most important thing for each of us is raise our children and strive to insure the next generation in our family does not inherit the denigration we ourselves have endured.”

Those who believe in Michael’s innocence have called out the media’s frenzied coverage of the case as a reason why he was seemingly convicted in the court of public opinion right away—and subsequently in a court of law—instead of given the presumption of innocence. But Dorthy Moxley appreciated the press’s persistence.

“I love the media,” she said. “It did so much to keep Martha’s case alive.” (In 2009, when Dominick Dunne died, Dorthy told Vanity Fair, “I have always said I had a team of angels helping me, and he was a very big angel on the team. Small in stature, but he was big.”)

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

“The Moxley family was absolutely lost and had nowhere to turn, so the media was where the pressure could be applied,” Len Levitt told Greenwich Time after the verdict. “That’s why I’ll never forgive the old management at [the newspaper] for what they did, for being cowardly and not running my initial piece when it should have run. If I hadn’t publicly insulted them and forced them to run it, I’m not sure it would have ever run. And I think now that that story really was a deciding factor.”

John Pisani, editor of Greenwich Time in 2002, said in reponse to Levitt that management was uncomfortable in 1982 with the story naming three men who hadn’t been officially identified by police as suspects.

“Michael was not mentioned as a suspect in the original story, and that legitimizes those earlier concerns,” Pisani said.

John Moxley, who was by his mother’s side throughout, gave his impression of Michael Skakel to the Hartford Courant: “He’s like a train wreck. I can’t stop looking at him. His whole family seems to be held together by the love of the checkbook. My parents gave my sister and I everything Michael didn’t have growing up.” John called the verdict “bittersweet. It’s a hollow victory.”

Michael ended up at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield, Conn.

“It’s a feeling of disbelief,” Stephen Skakel, who at the time was visiting Michael in prison every Saturday, told 48 Hours in 2003. “I love my brother and I believe in my brother 100 percent.”

And Skakel’s supporters didn’t go quietly.

His attorney filed a request for a new trial in August 2005; the conviction was upheld by Connecticut’s State Supreme Court in January 2006. In March they denied a request to rehear the appeal. That May, Skakel’s attorneys gave a judge the names of two men who had been implicated in the murder by Tony Bryant—who happened to be a cousin of NBA star Kobe Bryant.

After Robert Kennedy Jr. wrote an article for The Atlantic in 2003 arguing that his cousin’s conviction was a travesty, he started getting letters—including one, he said, that advised him to contact an old classmate of Skakel’s from the Brunswick School in Greenwich for information.

That classmate was Bryant, who said that two guys who he was out with in Belle Haven on Oct. 30, 1975, later bragged about committing the murder. Tony said that one had become “obsessed with Martha Moxley,” Robert Jr. told 48 Hours in 2013. Then, according to Bryant, the three of them had hung out briefly with a group that included Michael and Tommy before one picked up a golf club from the Skakels’ yard and said they were going to get a girl “caveman style.”

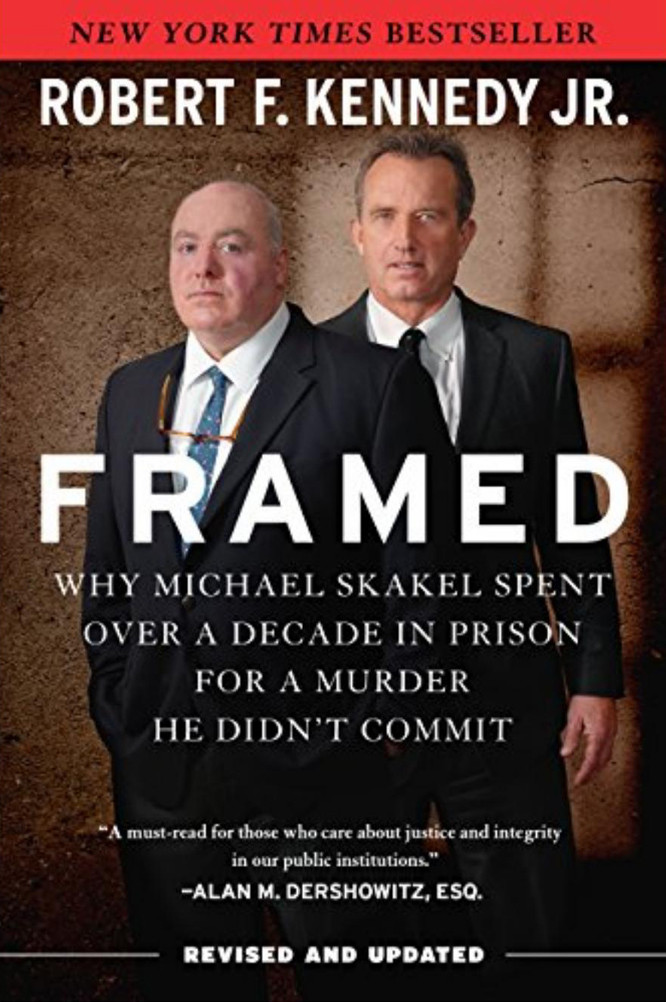

“For me, to come out publicly to defend somebody that basically everybody in the country feels is guilty of murder is, from a personal strategy, not probably a good choice for me,” Kennedy said. “But I know [Michael’s] innocent.”

Greentown author Tim Dumas noted in an update to his book that none of the kids Bryant mentioned from that night remembered seeing Bryant or his two companions. In fact, Dumas reported, Bryant himself said that the information he provided was “blown out of proportion.”

In July 2006, Skakel attorney Theodore Olson petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case, arguing that his client’s right to due process had been violated; they declined to take it up in November.

A year later, attorneys for Skakel requested a new trial on the grounds that the two men named by Bryant may have committed the murder; they were denied in October 2007.

Skakel’s team appealed the rejection to the State Supreme Court, which heard arguments in March 2009. In April 2010, a five-judge panel upheld the lower court’s decision, 4-1.

That September, his team again appealed, this time citing incompetent counsel at trial because defense attorney Michael Sherman, among other things, didn’t present all the evidence he could have to corroborate his client’s alibi, and he didn’t emphasize nearly enough that there was no physical evidence tying Skakel to the crime scene. Sherman stood by his handling of the case.

In January 2012 Skakel’s attorneys petitioned for a sentence reduction, arguing he should have been tried as a juvenile, because he was 15 when the murder occurred. A three-judge panel rejected the request in March.

He came up for parole for the first time in October 2012. Denied; he would be eligible again in five years.

Stephen, David and John Skakel all stood by their brother and insisted that the picture painted of them as spoiled, careless rich kids by media figures like Dunne was very unfair.

“He was the only one that I saw coming to court every day in a limousine,” Stephen said on 48 Hours, on which all three said that, as adults, they were leading modest lives. Back in the 1970s, John said, “it was a different time, a whole different life back then.”

Bob Luckey-Pool/Getty Images

But in October 2013, Superior Court Judge Thomas Bishop agreed that Sherman had done an inefficient job and vacated Skakel’s conviction, citing in his decision, among other things, Sherman’s “inexplicable” failure to introduce evidence that implicated Tommy Skakel, the police’s original suspect. “It would be an understatement to say that the state did not possess overwhelming evidence of [Michael’s] guilt,” he wrote.

Michael was released on $1.2 million bail in November 2013 pending the state’s appeal.

“Everybody in my family knows that Michael is innocent,” Robert Kennedy Jr. told the Associated Press at the time. “The only crime that he committed was having a bad lawyer.”

Prosecutors appealed in August 2014.

“This is a bad one,” Dorthy Moxley acknowledged to the Greenwich Sentinel in 2015 with the 40th anniversary of Martha’s death approaching. “It’s been 40 years, can you believe that? Forty years. Martha would be 55 today. I don’t torture myself by thinking what could have been and so forth. But all this hanging and waiting, it makes it harder.”

Meanwhile, Robert Kennedy Jr. wrote a book about the case, Framed, that came out in 2016, in which he insists his cousin had an airtight alibi and argues for the guilt of the two men named by Tony Bryant. (The original title was reportedly Media Lynching: The Persecution of Michael Skakel.)

“It is important for the public to know that these very same allegations have been thoroughly vetted in legal proceedings and found to be baseless,” Connecticut’s Division of Criminal Justice said in response. “Mr. Kennedy has no legitimate basis upon which to question the jury’s verdict.”

On Dec. 30, 2016, the Connecticut Supreme Court disagreed with the lower court judge and reinstated Skakel’s conviction, 4-3. After the judge who wrote the deciding opinion left the court, however, Skakel’s attorney asked them to reconsider.

On May 8, 2017, the court upheld the reinstatement. Skakel’s team immediately filed a request for them to reconsider.

Not until Jan. 30, 2018, did prosecutors go to court to request that Skakel’s bail be revoked; the court refused. Then, on May 4, 2018, the Connecticut Supreme Court vacated Skakel’s conviction and ordered a new trial.

“What do I want to say?” Dorthy Moxley told the New York Times. “Well, I am surprised and not particularly happy about this. But we’ll handle and do what we have to do.”

Catrina Genovese/Getty Images

The state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in January declined to consider it, meaning Skakel’s conviction remains vacated.

“Over the past 10 years, two Connecticut courts—including the Connecticut Supreme Court—have painstakingly reviewed every detail of Michael Skakel’s case,” his appellate attorney Roman Martinez told reporters. “Both reached the same conclusion: Michael’s conviction violated the U.S. Constitution.”

“The state of Connecticut had a very, very, very good case, and we absolutely know who killed Martha,” countered Dorthy Moxley. “If Michael Skakel came from a poor family, this would have been over. But because he comes from a family of means they’ve stretched this out all these years.”

The option to retry him is still open to Connecticut prosecutors, but the possibility is growing ever more unlikely as the years go by.

Now in her 80s and living in New Jersey, Dorthy Moxley continues to take opportunities, such as Oxygen’s The Case of Martha Moxley, to ensure that her daughter isn’t forgotten—though, as she told Laura Coates, she doesn’t usually bring up that she once had a daughter when she meets new people who have no idea who she is.

“I don’t burden new friends with my sorrows,” she said, “but the people that she knew and who loved her will always love her. A lot of people just can’t handle it. You just learn how to live with it.”

(E! and Oxygen are both members of the NBCUniversal family.)

Be the first to comment