Scandal works in mysterious ways.

It can alternately make people famous forever or relegate them to the dustbin of relevance. Give them an indelible mark next to their names for posterity or, at the end of the day, just serve as a blip in a life story.

But either way, scandal has a long shelf life. A story’s timeliness can actually bounce around from era to era, hiding in plain sight for years before it’s determined that it’s a story that needs revisiting. And now seems to be the time that every crime, misstep and mystery is primed for a retelling, with Hollywood cranking out project after project to satiate a public more eager than ever to find answers to the questions of “why?” and “how?”

A truly bizarre chapter in not just the teeming Kennedy family history but in American history in general, the story of the accident that occurred on July 19, 1969, on Chappaquiddick Island and its aftermath is one for the ages. At the time, however, it shared a news cycle with the Apollo 11 moon landing the next day, and then the murders of Sharon Tate and six others by the Manson family barely three weeks later.

And with the 50th anniversary of these wildly different yet still poignant events upon us, history has understandably repeated itself. Chappa-what?

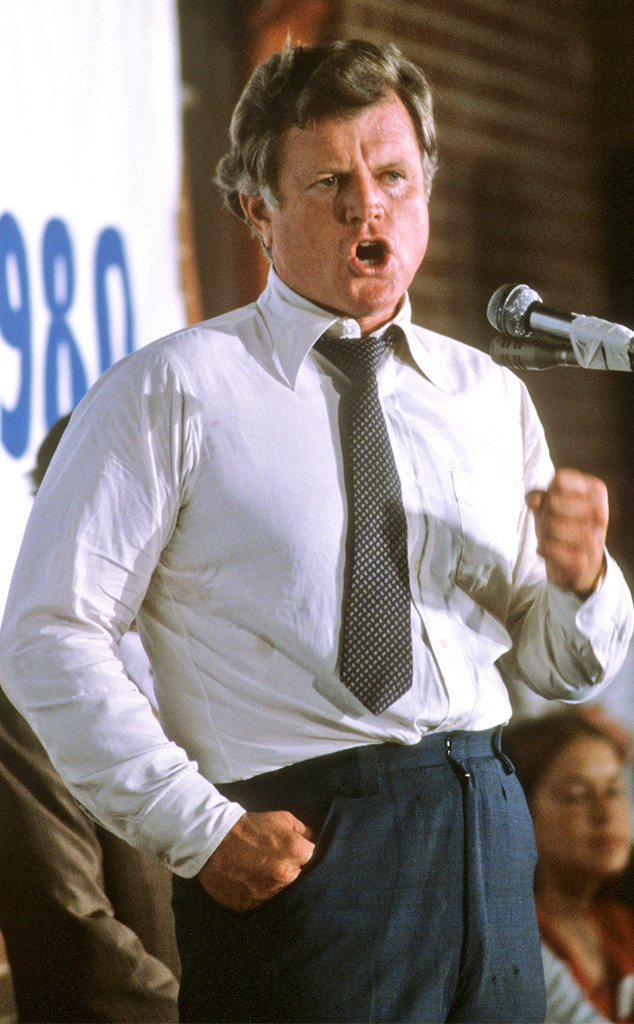

Ted Kennedy, the youngest of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. and Rose Kennedy‘s nine children, had his eyes on the presidency—and the Kennedys’ stalwart supporters, devastated by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and the murder of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy while he was campaigning for the Democratic nomination in 1968, had great hopes for the 30-year-old senator from Massachusetts as well.

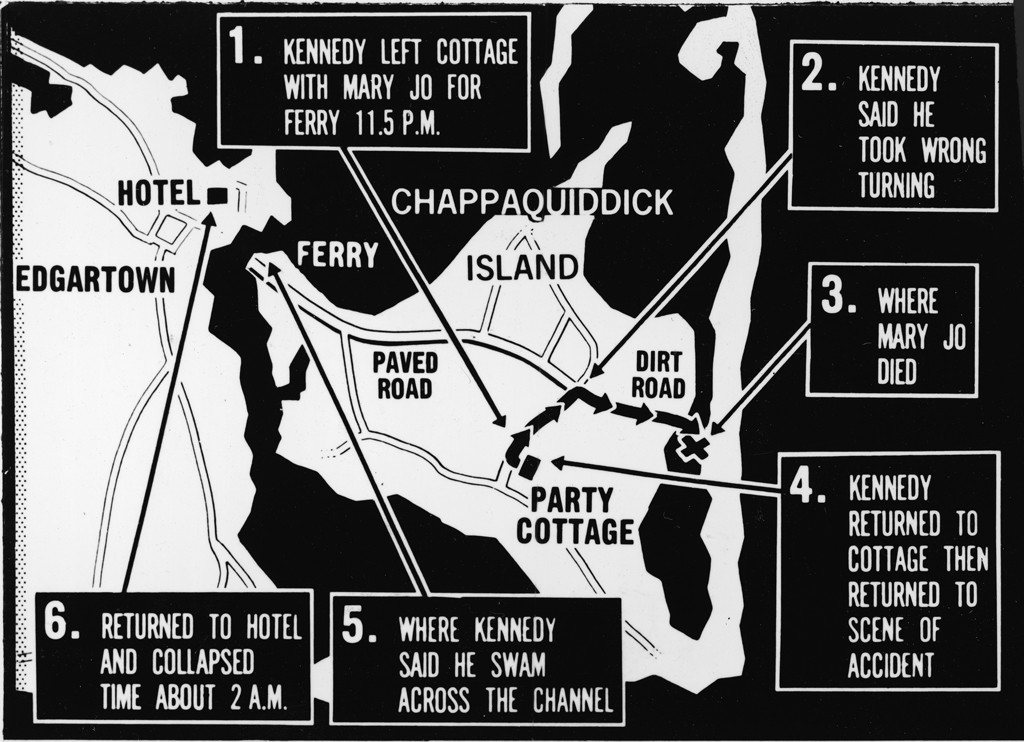

Chappaquiddick Island is a 150-yard ferry ride from Edgartown, Mass., on the east end of Martha’s Vineyard, a popular vacation destination for the world’s elite, including numerous U.S. presidents. It measures about 3 miles across and there was only one paved road, Chappaquiddick Road. A hairpin turn led you to Dike Road and a narrow wooden bridge that traversed Poucha Pond.

On the morning of July 19, 1969, a couple of fishermen noticed a car overturned and submerged up to its tires in the pond. They knocked on the door of a nearby cottage and the tenant, who with her husband was renting the place, called police at around 8:20 a.m. She would tell Edgartown Police Chief Dominick James Arena, who responded alone to the call and actually borrowed bathing trunks belonging to the woman’s husband and dove into the water himself to get a closer look, that she remembered hearing a car that sounded as if it were going awfully fast at around midnight. But she didn’t hear a splash or anything else that indicated an accident had happened.

Arena radioed for a fire department diver and another officer and when various backup personnel arrived at 8:45 a.m., they put a trace out on the car’s license plate, L78207.

The vehicle was registered to Edward M. Kennedy.

Brooks Kraft LLC/Sygma via Getty Images

According to Leo Damore‘s comprehensive 1988 book Chappaquiddick: Power, Privilege, and the Ted Kennedy Cover-Up (originally called Senatorial Privilege: The Chappaquiddick Cover-Up), Arena’s initial thought was that the Kennedy family had just suffered another tragedy. No one had contacted authorities about an accident, presumably because whomever had been in the car when it went off the bridge was dead.

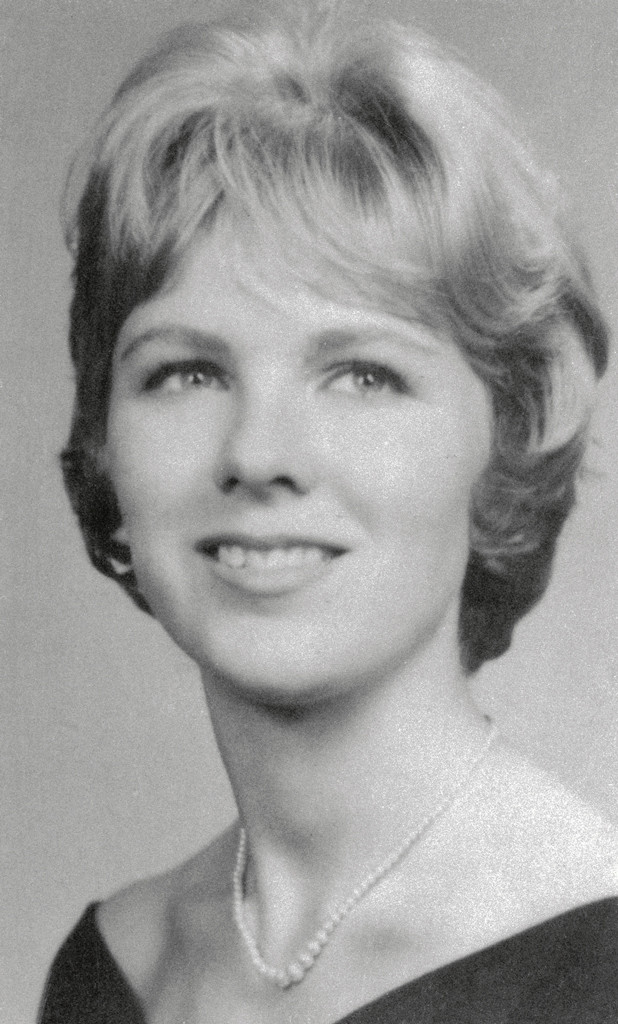

The diver saw that the front seat was empty. Then he spotted two sandal-clad feet through the right rear window. They belonged to 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne.

Kopechne, a college-educated teacher turned activist and political consultant from Pennsylvania, had been a member of Bobby Kennedy’s staff when he became a U.S. senator in 1964 and had worked tirelessly on his presidential campaign. His death in June 1968 at first made her want to quit politics, but she returned to Washington, D.C., set up with a couple of roommates and got a job with a political consulting firm.

After Kopechne’s death, Ethel Kennedy, Bobby’s widow, called her a “sweet, wonderful girl.”

Bettmann/Getty Images

She met Sen. Ted Kennedy on the night of July 18, 1969, at a party thrown in a cottage on Chappaquiddick rented by attorney and Kennedy cousin Joe Gargan. Kopechne and five girlfriends—they had all worked on RFK’s campaign and, along with several others, were known as the “Boiler Room Girls”—had checked into three rooms at a motel in Edgartown for the weekend. Gargan, who worked on the campaign as well, had previously hosted the Boiler Room Girls, including Kopechne, in 1968 after Bobby died to help get everyone’s mind off their grief and they had such a good time they planned a reunion.

Kennedy arrived on Martha’s Vineyard that day for the Edgartown Yacht Club Regatta, in which he competed with the late JFK’s former boat, Victura. His wife of more than 10 years, Joan (née Bennett), was at home, pregnant with their fourth child.

“Jeez, I’ve never been so tired in my life,” Kennedy told friend and congressman Tip O’Neill, who had flown in with him that day, as O’Neill recalled to Edward Klein for his 2009 book Ted Kennedy: The Dream That Never Died.

According to multiple accounts, in hindsight at least people close to Ted Kennedy could feel in the weeks and months leading up to the accident that something was wrong with him. Already known as a drinker, he had been drinking even more, and, like his father and big brother JFK, he wasn’t doing much to keep his womanizing a secret. Traumatized by the loss of his brothers, he was telling people he was considering getting out of politics altogether.

Per Klein’s book, in April 1969 he got drunk—sipping from his late brother Bobby’s flask—while on a plane coming back from Alaska with a group of fellow senators, and he was only saved from national embarrassment when the media showed up to greet the plane because his 1 1/2-year-old son Patrick J. Kennedy II (future congressman from Rhode Island) toddled over to him for a hug. The father-son moment won the day.

So in July 1969, Ted Kennedy was apparently a mess.

But his spirits started to perk up once he got to Gargan’s cottage and went swimming with the young ladies. Kopechne and her friends watched the regatta on a boat rented by Paul Markham, the former U.S. State’s Attorney for Massachusetts and another longtime Kennedy friend.

That night the party consisted of Kopechne and her five female friends, all of them single, and six mostly married men, including Kennedy, Markham, Gargan and 63-year-old Jack Crimmins, a legal aide serving as Ted’s chauffeur for the weekend (Teddy was also said to be a terrible driver on his best day).

Varying levels of alcohol were consumed, depending on whom you asked. “It was a steak cookout, not a Roman orgy. No one was drinking heavily,” said partygoer Esther Newberg, per Klein. But Gargan said Crimmins and Markham were drinking heavily, and Crimmins said to Kennedy, more out of tiredness than malice, “I don’t give a s–t how you get home, Kennedy. I’m not driving you.”

According to Joe McGinniss‘ 1993 book The Last Brother, Ted drank beer during the sailing race; drank three rum-and-Cokes during the ritual congratulatory toast for the winner, Ross Richards; and, before he went to the party, he drank some beer with friends at his room at the Shiretown Inn.

So Kennedy—whom witnesses said only had two or three rum and Cokes that night—took the keys of his 1967 Oldsmobile Delmont 88 from Crimmins and hit the road. Kopechne went with him and didn’t take her pocketbook, an indicator that they planned to return to the cottage.

By the time Kennedy was being questioned by police the next morning, his remaining blood-alcohol level wouldn’t have been an accurate representation of his condition—and no one ever tested it anyway. Kopechne’s blood-alcohol level registered at .09 percent, indicating she’d consumed at least a couple of drinks within an hour before leaving the party. Though some who knew her painted a picture of a woman who was so devoted to her work she was practically celibate, Kopechne had actually just broken up with a longtime boyfriend before the weekend getaway, so she could have been open to a late-night swim with the senator.

Per McGinniss, the manager of the Shiretown Inn was the first non-partygoer to see Kennedy after the accident, noting that he saw him seemingly coming downstairs from his room at 2:25 a.m. on the morning of July 19. Kennedy seemed out of sorts and said he had heard party noise coming from the room next door. He asked what time it was.

A desk clerk recalled seeing Kennedy again at around 7 a.m., dressed in casual yacht wear and freshly shaven. The senator used the pay phone to call a girlfriend in Florida, then ran into some friends, including the regatta winner Ross Richards. At about 8 a.m., Joe Gargan and Paul Markham showed up. “Joey looked awful,” Richards’ wife told Leo Damore. “His clothes were all wrinkled, and his hair was sticking out.” Both men looked soaking wet, Richards later told police.

Dispatched to look for Kennedy, Chappaquiddick resident Antone Bettencourt (the owner of the cottage were the original call to police was made) caught up with Kennedy at around 9:30 a.m. at the ferry landing in Edgartown. Markham and Gargan were with him. In the meantime, responders were still searching the pond, figuring there may be another body to recover.

According to Damore, when asked if he knew that a dead girl had been found in his car and would he need a ride to the bridge, the senator replied, “No, I’m going on over to town.

Which he then did.

Harvey Ewing, Vineyard bureau chief for the New Bedford Standard-Times, snapped Kennedy’s picture as he disembarked from the ferry. Ewing told Damore that the senator looked to be “in fine shape.”

When Chief Arena called into the Edgartown Police Station to reiterate the need to find Kennedy, it turned out the senator was already there. Over the phone, Kennedy asked Arena to meet him at the station. Still damp from his dive into the pond, Arena hitched a ride with Dr. Edward Self, president of the local residents’ Chappaquiddick Association, into town. Kennedy was “poised, confident, and in control. Using my office and telephone. And I’m standing in a puddle of water in a state of confusion,” Arena told Damore.

It was there that Kennedy told Arena that he had been driving, completely throwing the police chief for a loop.

Meanwhile, Dr. Donald Mill, Edgartown’s associate medical examiner, had made the preliminary determination at the scene that they had “an obvious and clear” drowning on their hands, having found no signs of other trauma to the body. He was confident in his conclusion, but he said, due to the prominent people the deceased (who had not yet been identified) appeared to be associated with, he’d defer to the District Attorney regarding the need for an autopsy.

Ultimately, there was no autopsy. (A subsequent petition from the DA to exhume the body and conduct an autopsy was denied that December, with Kopechne’s parents supporting the decision.)

Also on July 19, phones were ringing all over Massachusetts, alerting assorted Kennedy family cohorts and aides that there had been a fatal accident involving Ted’s car. During one call it was determined that Mary Jo Kopechne’s parents needed to be notified. Ted also told his chief aide to contact someone on the island to ensure that Kopechne’s body be transported off of Martha’s Vineyard as soon as possible—and that her five friends also be informed that they shouldn’t speak to anyone about that night for the time being.

Having set up an impromptu office at the police station, Kennedy dictated a statement to Markham, which Arena took to type up himself because everyone was busy answering the nonstop phone calls.

“On July 18, 1969, at approximately 11:15 p.m…I was driving my car on Main Street on my way to get the ferry back to Edgartown,” the statement read, per Damore. “I was unfamiliar with the road and turned right onto Dike Road, instead of bearing hard left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately one-half mile on Dike Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge. There was one passenger with me, one Miss Mary — [he had told Arena he wasn’t sure of the spelling of her last name], a former secretary of my brother, Sen. Robert Kennedy. The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and the window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt. I was exhausted and in a state of shock. I recall walking back to where my friends were eating. There was a car parked in front of the cottage and I climbed into the back seat. I then asked for someone to bring me back to Edgartown. I remember walking around for a period of time and then going back to my hotel room. When I fully realized what had happened this morning, I immediately contacted the police.”

Kennedy told Arena he wanted to speak to his attorney Burke Marshall before they released the statement.

Arena told Damore that saying yes to Kennedy in that moment and delaying the many questions he had for him—such as why the accident wasn’t reported for more than nine hours—was “something of a low point in my particular case.”

In the moment, however, Arena helped arrange for a small private plane to take Kennedy back to his home in Hyannis Port, a 10-minute flight.

But after a few hours went by and Arena hadn’t yet heard back from the Kennedy camp, he read the statement to reporters at 3 p.m. He also said the senator had been “cooperative” and speculated that being in a “state of shock” could have accounted for the nine-hour delay in reporting the accident.

Central Press/Getty Images

With utmost irony, considering putting a man on the moon before the 1960s were over had been one of JFK’s primary goals for the U.S. space program, a rapt audience tuning in to watch live coverage leading up to Neil Armstrong taking humanity’s first steps on the moon, saw the broadcast briefly interrupted by a news bulletin coming out of Martha’s Vineyard.

Long before the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Eve, the ’60s had ended, butchered by the Manson family, shipped out to Vietnam, washed away under a bridge on Chappaquiddick.

Per McGinniss, the first Boston-area headlines about the accident indulged their hometown boy and at first Ted Kennedy thought that the accident might not damage him politically, that he could still run for president in 1972.

But it was only hours before the press found out what Kennedy had been doing on the island—partying with a group that included six young women, which he had neglected to mention in his statement. His press secretary Dick Drayne characterized the gathering as being more in honor of Bobby Kennedy than a post-regatta bacchanal.

“Ted came by to thank the girls,” Drayne told a reporter. “Then this one girl had to leave and they were trying to catch a ferry when the accident happened.” Drayne even threw in that Joan Kennedy had been planning to join her husband the next day.

Reporters also recreated that fateful drive and concluded themselves that it was highly unlikely that Kennedy mistakenly turned where he said, and that he must have been headed for the beach, not the ferry. Not to mention, there was a house—where the two fishermen went to call the police—right there. And, as McGinnis wrote, there were actually three houses Kennedy would’ve had to pass before returning to the cottage where the party was.

Local resident and Deputy Sheriff Christopher “Huck” Look told reporters on July 21 that at about 12:40 a.m. on the night of the accident (also not in keeping with Kennedy’s statement) he witnessed a car with a man driving, a woman in the passenger seat and “either another person or some clothing” in the back seat go from the paved main road onto a dirt path, then back up to the road, and then take off toward the bridge. At the scene of the accident on July 19, he had identified the Oldsmobile as the car he’d seen.

Express Newspapers/Getty Images

Then the diver who first found Kopechne’s body told reporters that she was in “a very conscious position,” not one that looked as if she’d been knocked out by a crash, but rather with her face pressed to the floorboards, as if she’d been trying to keep her face out of the water for as long as possible, the car having flipped over.

If help had arrived sooner, he surmised, “there was a good chance the girl could have been saved.”

Meanwhile, all sorts of Kennedy family confidantes and legal and political power brokers, including former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, were piling into Hyannis Port to manage the fallout of this potentially career-ending debacle.

David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

And, when you think about how Ted Kennedy went on to become the “liberal lion” of the U.S. Senate, a position he’d hold for the rest of his life until he died of brain cancer in 2009, they managed the fallout remarkably well.

He pleaded guilty to a single charge of “leaving the scene of an accident without negligence involved” and received a suspended two-month jail sentence. He’d go on to be revered as the consummate deal-maker, a tireless champion of progressive causes, including affordable health care and women’s rights, as well as a legislator who could negotiate across the aisle and get things done. His checkered past was no secret, but like so many larger-than-life figures, it was accepted as part of the legend.

In an article about the 1994 Senate race, Kennedy’s seventh rodeo, the New York Times referred to “the distant but still damaging memory of the accident at Chappaquiddick Island that caused the death of 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne.”

Images Press/IMAGES/Getty Images

But the damage was palpable at home, and the scandal burrowed into the fabric of all the Kennedy suffering that had come before.

Kennedy, wearing a neck brace, attended Kopechne’s funeral on July 23 with wife Joan and Ethel Kennedy, the senator’s presence attracting a horde of spectators outside the church. The next day the chief medical examiner of Edgartown issued a statement saying his assistant had been wrong not to order an autopsy.

On July 25, after entering his guilty plea and avoiding jail time, Kennedy finally broke his silence on the accident to reporters.

“There is no truth, no truth whatever, to the widely circulated suspicions of immoral conduct that have been leveled at my behavior and hers regarding that evening,” he said in his nationally televised remarks from the library of his parents’ home. “There has never been a private relationship between us of any kind. I know of nothing in Mary Jo’s conduct on that or any other occasion—the same is true of the other girls at that party—that would lend any substance to such ugly speculation about their character. Nor was I driving under the influence of liquor.”

He maintained they left at 11:15 p.m. but abandoned the part about making a wrong turn because he was unfamiliar with the road. Once they went off the bridge and he managed to get out of the car, he “made immediate and repeated efforts to save Mary Jo by diving into the strong and murky current, but succeeded only in increasing my state of utter exhaustion and alarm.” He claimed that his doctors had informed him afterward that he’d suffered a concussion. He called his failure to report the accident immediately “indefensible.”

He said that once he got back to the cottage, Kennedy said, he asked Joe Gargan and Paul Markham to go with him to the pond to look for Kopechne. “Their strenuous efforts, undertaken at some risk to their own lives, also proved futile,” he said.

“All kinds of scrambled thoughts—all of them confused, some of them irrational, many of them which I cannot recall, and some of which I would not have seriously entertained under normal circumstances—went through my mind during this period,” Kennedy continued. “They were reflected in the various inexplicable, inconsistent, and inconclusive things I said and did—including such questions as whether the girl might still be alive somewhere out of that immediate area, whether some awful curse did actually hang over all the Kennedys, whether there was some justifiable reason for me to doubt what had happened and to delay my report, whether somehow the awful weight of this incredible incident might in some way pass from my shoulders. I was overcome, I am frank to say, by a jumble of emotions—grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion, and shock.”

Kennedy then said he had Markham and Gargan drive him to the ferry crossing and, finding it too late for a boat, he jumped into the water and swam the 150 yards to get back to his hotel on Martha’s Vineyard, “nearly drowning once again in the effort.” He returned to his room at 2 a.m. but did remember venturing out and saying something to a hotel employee.

A E Maloof/AP/Shutterstock

He implored the voters of Massachusetts to let it be known if they wanted him to resign. Then he quoted his brother John Kennedy’s (ghostwritten) Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Profiles in Courage, before concluding, “I pray that I can have the courage to make the right decision. Whatever is decided, whatever the future holds for me, I hope that I shall be able to put this most recent tragedy behind me and make some future contribution to our state and mankind, whether it be in public or private life. Thank you and good night.”

That night, while Mary Jo Kopechne’s father called Kennedy’s explanation “not enough,” her mother stated briefly, “I am satisfied with the Senator’s statement—and do hope he decides to stay on as Senator.”

Kennedy returned to work on July 31.

Six days before the inquest into Kopechne’s death was to begin in September, Joan Kennedy suffered a miscarriage, her third overall. When it happened Ted was on a camping trip with their two eldest children on Nantucket, but he rushed to the hospital to be by her side.

The inquest was postponed until Jan. 5, 1970. For three days, Kennedy and 26 other witnesses gave sealed testimony. A grand jury was convened in April and it returned no indictments, after which the testimony was unsealed. On Nov. 4, 1970, Kennedy was re-elected to the U.S. Senate.

Ted and Joan divorced in 1982. He remained a hard-living bachelor until 1992, when he married attorney Victoria Reggie. He was 62, she was 40, and the divorced mother of two provided a by then much-needed shot in the arm to Kennedy’s public appeal.

“Think how much more difficult this campaign would be without her. Picture Ted Kennedy campaigning alone,” Democratic consultant Ann Lewis told the Times in 1994. “Ted Kennedy campaigning with Vicki is a far stronger campaign. It conveys an image of him in an obviously settled, happy relationship. It’s an image we want to see.”

“I was always a Kennedy Democrat,” Vicki Kennedy, whose father had campaigned for JFK, RFK and Ted when he ran for the Democratic nomination against President Jimmy Carter in 1980, said at the time. “The entire family was very taken with them. Part of our political upbringing was the Kennedys. They were terrific leaders, inspirational.”

Vicki would see Ted sailing from Hyannis Port to her family’s home on Nantucket. “I thought he was really interesting, funny and nice,” she told the Times. “I didn’t fall instantly, madly in love.” Since, however, “he has lifted my life in a way that’s really unbelievable. He is such a caring, nurturing, understanding person.”

Asked about his notorious past, she said, “I reject strongly the label of my husband as a womanizer. I know him. I know the tremendous respect he has for me, and for his daughters, and for his mother. I think that says it all.”

It also says that, once upon a time, there were no limits to the influence of the Kennedy dynasty. But all reigns come to an end eventually.

(Originally published April 5, 2018, at 7 a.m. PT)

Be the first to comment