So few things are certain these days, but a fact we could always count on is that Charles Manson was evil incarnate.

Still a perfectly fair synopsis. But as we’ve reached 50 years since five followers from the cult that was later dubbed his “Family,” butchered seven people over the course of two nights in August, the story of why this all happened has started to shift with regard to the complicated mythology behind the motive that was officially given for his and his minions’ most infamous crimes.

And it’s not as if the motive detailed in court—the triggering of “Helter Skelter”—was some sort of logical answer as to why and how these murders took place, either.

“There’s an element of it that remains unsolved, that keeps people talking about it,” filmmaker James Buddy Day, author of the new book Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson, told E! News, as we compared the as yet bottomless interest in Manson to the fascination that follows infamously unsolved cases, such as that of Jack the Ripper and the Zodiac killer.

“Obviously we know who committed the murders in the Manson case, it’s not unsolved in the same way, but the idea that there’s more to the story just keeps people talking about it.”

But the gruesome facts remain the same: Shortly after midnight on Saturday, Aug. 9, 1969, Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, and Linda “Darling” Kasabian scaled the hillside leading up to 10050 Cielo Dr., a relatively isolated hilltop property nestled in Los Angeles’ Benedict Canyon. Tex cut the telephone wire and they proceeded up the driveway, where they encountered 18-year-old Steven Parent‘s Rambler Ambassador.

Parent was the first one killed, shot by Watson in the driver’s seat of his car after visiting the guest house to see William Garretson, the property caretaker, to see if he wanted to buy a piece of stereo equipment. His watch strap was severed and he had a slash wound on his palm from where he first tried to shield himself from Watson’s knife.

It’s just a freak occurrence that Parent was there—though, really, every single bit of what transpired was a freak occurrence.

The killers went into the house, which had been rented that February by filmmaker Roman Polanski (who was in London finishing The Day of the Dolphin) and his wife, actress Sharon Tate. Voytek Frykowski, an actor friend of Polanski’s from Poland, was asleep on the couch in the living room. His girlfriend Abigail Folger was in the guest bedroom reading. Tate, 8 1/2 months pregnant, was in her room talking to Jay Sebring, hairstylist to the celebrity set and a former boyfriend. Watson, Atkins and Krenwinkel gathered everyone into the living room, where they tied one end of a rope around Tate’s neck, tossed it over a ceiling beam and tied the other end around Sebring’s neck.

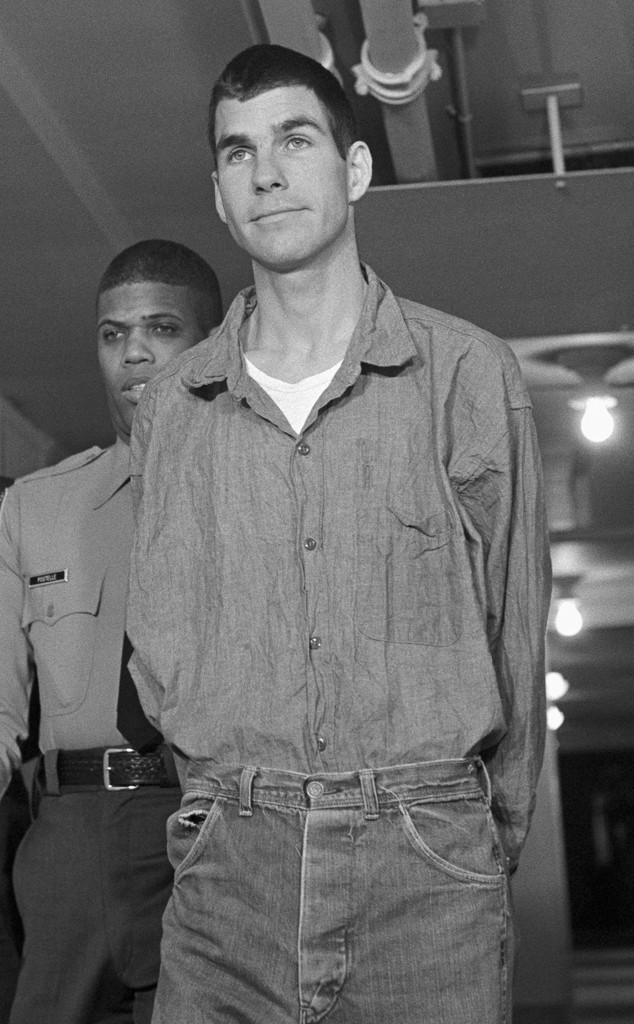

Bettmann / Contributor

Watson shot Sebring when he tried to fight for his life, then stabbed him multiple times. Frykowski struggled with Atkins, who started stabbing him in the legs, but he managed to get outside, where Watson, the only one carrying a gun, shot him twice and then bludgeoned him with the butt of his revolver. He ended up with 51 stab wounds. Folger managed to get loose and was halfway across the front lawn when Krenwinkel caught up with her and stabbed her 28 times. Tate, being held down by Atkins, was the last to die. They stabbed the Valley of the Dolls star 16 times.

Watson drove that night, but Kasabian—who had only known Manson for about a month—seemingly was picked to go along because she had a valid driver’s license. She later testified that Watson first had her check for unlocked doors or windows and, when she told him without having checked that everything was locked, he told her to go back to Parent’s car and act as lookout. She said that she ran toward the house when she heard the screams and witnessed the carnage. She was initially charged with murder along with everyone else but eventually was granted immunity and became the prosecution’s star witness.

The murderers slept through most of the next day, Saturday, Aug. 10. Late that night, Manson, Atkins, Kasabian and Steve “Clem” Grogan dropped Krenwinkel, Watson and Leslie “Lulu” Van Houten off at 3301 Waverly Dr., in L.A.’s Los Feliz neighborhood. Manson and other Family members had previously been to the house next door, which belonged to future prosecution witness Harold True, but Manson didn’t want to be connected to what was about to transpire, so he settled for the neighbors’ house.

Later according to Watson, he and Manson went inside and Charlie tied up Leno LaBianca, owner of a chain of grocery stores, and his wife Rosemary. Then Manson walked out and Krenwinkel and Van Houten went in and joined Watson in stabbing the couple to death.

Someone carved the word “WAR” into Leno’s stomach and left a fork sticking out of his belly, and they wrote in blood again: “rise” and “death to pigs” on the wall and, most consequentially despite the misspelling, “Healter Skelter” on the refrigerator.

Ezio Praturlon/Shutterstock

“FILM STAR, 4 OTHERS DEAD IN BLOOD ORGY: Sharon Tate Victim in ‘Ritual’ Murders,” a local headline blared. An initial CBS report described the killings as “reminiscent of a weird religious rite.” Incorrect details about the crime scene ran amok, from reports saying there were hoods (as opposed to pillow cases) over the victims’ heads, or that Tate and Sebring had x’s carved in their bodies, or were sexually mutilated. Tate was at one point called “a dabbler in satanic arts,” and the macabre aspects of her husband’s films became the topic of even more chatter.

Hollywood was beside itself with fear, not knowing whether Tate’s death was part of a greater plot targeting famous people. Mia Farrow, who starred in Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, was said to be too distraught to attend Sharon’s funeral, and Steve McQueen, a friend and client of Sebring’s, started carrying a gun.

The fraught atmosphere lingered until authorities announced in December that they had suspects in custody. And even then, nothing would be the same.

Susan Atkins, in jail after being arrested during a raid of the Family’s latest home, Barker Ranch, had talked nonstop to her cellmates about what she had done, a key piece of the puzzle as authorities scrambled to put it all together. She claimed there was indeed a celebrity kill list that included McQueen, Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton and Tom Jones, but aside from her rambling there was no evidence it ever existed.

More than anything else, it was simply terrifying and hopelessly random that Tate and her friends, Parent and the LaBiancas were caught up in the deadly vortex of whatever Manson was trying to achieve.

Which, according to the prosecutor who put him in prison for the rest of his life, was the triggering of a race war between blacks and whites, an uprising that Manson referred to as “Helter Skelter,” a term he got from the Beatles song of the same name along with various other messages gleaned from the Fab Four’s White Album. As explained by L.A. Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi, the war would ultimately lead to Manson being the master of everyone who survived—he reasoned that it would be black people who conquered the whites, but then they wouldn’t know what to do with themselves. Enter Manson, who would be hiding out with his family in the desert until the war was over, as supreme leader.

Considering the type of person Manson was, the theory proved believable. He was immediately linked to the hippie counterculture, one of the reasons why the Tate-LaBianca murders are considered one of the death knells for the 1960s, but not even Manson—a self-educated conman who considered a message of peace and love weak; who advocated violence; and who was, for starters, racist, anti-Semitic and misogynistic—considered himself a hippie.

“Charles Manson was one of the most virulent racists that ever walked the planet,” Jeff Guinn, author of Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson, told Newsweek in 2017. “I keep being reminded of Charlie Manson when we see white supremacist groups. It’s almost like they’re copying the Charles Manson playbook. He’s certainly acting as a role model for people today.”

Bugliosi, who successfully prosecuted Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten in one trial and Watson in another, acknowledged that “Helter Skelter” was an “incredibly bizarre motive,” but that didn’t make the fact that Manson believed it any less true, he said.

In his closing argument at the end of the 11-month-long first trial, during which the defense called no witnesses but Manson insisted on taking the stand, Bugliosi said: “Keep this in mind, ladies and gentlemen, that murders as extremely bizarre as these murders were, almost by definition—by definition—are not going to have a simple, common, everyday type of motive. Just imagining the incredible barbarism and senselessness of these murders would leave one to conclude that the person who masterminded them had a wild, twisted, bizarre reason for ordering them.

“The evidence at this trial shows that Charles Manson is that person who had that motive, and the trial showed what that motive was. I, as a prosecutor, and you folks as members of the jury, cannot help it, we cannot help it if Manson had this wild, crazy idea about Helter Skelter. It is not our fault. Manson is the one that made the evidence, not we. We can only deal with the evidence that presents itself.

“That evidence was that he wanted to start this black-white war out in the streets. That is what the evidence was that came from that witness stand. On the very day of the Tate murders, a matter of hours before these five murders, Linda Kasabian testified that Manson said: ‘Now is the time for Helter Skelter.'”

Paul McCartney didn’t play “Helter Skelter” in concert for years, until eventually, he told NME last September, “I thought, you know, that’d be good on stage, that’d be a nice one to do, so we brought it out of the bag and tried it and it works. It’s a good one to rock with, you know.” (U2 reclaimed the music first, with Bono announcing at the beginning of 1988’s Rattle and Hum, “This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles. We’re stealing it back.”)

But several new books delving into the Manson case all poke holes in the Helter Skelter motive. They mainly render the reason for the murders less complicated, though no less cold-blooded, yet one somehow makes the story even more bizarre. Apparently that was possible.

“My goal isn’t to say what did happen—it’s to prove that the official story didn’t,” Tom O’Neill writes in his 20-years-in-the-making Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties.

AP Photo

The book includes O’Neill’s account of a face-to-face showdown with Bugliosi (who died in 2015) in the latter’s kitchen that took place in 2006, in which the author of Helter Skelter, the definitive book on the Manson case, tells O’Neill, “It’s a tribute to your research. You found something that I did not find…Some things may have gotten past me. [But] I would never in a million years do what you’re suggesting. Okay? Never. My whole history would be opposed to that. And number two… It’s preposterous. It’s silly.”

What O’Neill was suggesting was that Bugliosi suborned perjury as part of a bigger cover-up that encompassed his office, law enforcement and, yes, the CIA.

He poses that Bugliosi avoided asking record producer Terry Melcher—who had met Manson, a prolifically uneven songwriter, through Dennis Wilson; had been unimpressed by Manson’s music and wasn’t inclined to help him get noticed; and who had been the previous tenant of 10050 Cielo Dr. before Tate and Polanski moved in—tougher questions on the stand about his association with Manson, keeping what could have been a more logical connection to Cielo off the table.

“This throws a different light on everything… I just don’t know what to believe now,” former Deputy District Attorney Stephen Kay, one of Bugliosi’s fellow prosecutors on the case, tells O’Neill after seeing Bugliosi’s handwritten notes, unearthed by the writer. “If [Vince] changed this, what else did he change?”

O’Neill points out that multiple Family members, including Manson, were first rounded up on Aug. 16, 1969, a week after the murders, in a raid at Spahn Ranch (authorities had actually been surveilling the Ranch to gather evidence of an auto-theft ring) and then released two days later (because the warrant was misdated, a technicality, according to Bugliosi’s book).

Based on numerous interviews he conducted, O’Neill broaches the possibility that authorities knew that Manson was dangerous (as well as on parole and seemingly guilty of auto theft) but let the Family run amok, thinking that they might help usher in counterculture fatigue as opposition to the Vietnam War was heating up. At worst, in their eyes, they thought he might attack some Black Panthers.

Former Sheriff’s Detective Preston Guillory told O’Neill that there had been a standing order from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Office in 1969: “Make no arrests, take no police action toward Manson or his followers.” Guillory (who left the LASO that December) guessed that the Aug. 16 raid and subsequent arrests were intended to lessen the impression that officers had been standing idly by while people drove in and out to commit murder. But then all the charges were dropped a few days later.

In his 1993 autobiography Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counterculture, Paul Krassner (who just died in July), recalled Guillory telling him in a similar-sounding conversation about the Manson case, “It appeared to me that the raid was more or less staged as an afterthought…So the hypothesis I put forward is, either we didn’t have them under surveillance for grand-theft-auto because it was a big farce, or else they were under surveillance by somebody much higher than the Sheriff’s Department, and they did go through this scenario of killing at the Tate house and then come back, and then we went through the motions to do our raid. Either they were under surveillance at the time, which means somebody must have seen them go to the Tate house and commit the killings, or else they weren’t under surveillance.”

“I think he’s very much looking for conspiracies and cover-ups that aren’t there,” Day says of O’Neill, “and he actually seems to ignore everything that I think is important, which is the inner workings of the Manson family, the dynamics of the people who are involved.”

But in another respect, the authors’ research took them in a similar direction, one that ended in the unraveling of “Helter Skelter” as a motive.

“At the time it seemed to make sense to people,” Day says. “In the 50 years since, with the invention of the Internet and the access to the case files, once you start to dig into all that, it starts to unravel really quickly. And then it leaves you asking, ‘OK, well, if this isn’t really what happened, then what did happen?'”

“Manson told the killers to stage the Tate-LaBianca murders to look like they were the work of militant Black Panthers,” writes Ivor Davis in his new book Manson Exposed: A Reporter’s 50-Year Journey into Madness and Murder. “And not because he wanted to start a race war in America, inspired (Manson claimed) by the Beatle lyrics in songs like ‘Helter Skelter,’ ‘Piggies’ and ‘Revolution.’ His hope was the police would release Robert.”

“Robert” being Robert, or Bobby, Beausoleil, who was in jail on the night of Aug. 8, having been arrested for the July 27, 1969, murder of music teacher Gary Hinman, at whose home the words “political piggy” were written on the wall in blood. Davis posits that Manson sicced his followers on the Tate and LaBianca homes to kill and leave behind a similar signature, to make police think that Hinman’s real killer was still out there.

Family member Mary Brunner told police that the use of the word “pig” was a ruse to make them suspect members of the Black Panthers, who had used that word to describe cops, were behind the killings. When he was first arrested, Beausoleil also unconvincingly suggested that the Black Panthers were responsible, that he had bought the Fiat he was driving, in which police found the murder weapon, from a Black Panther.

Susan Atkins, meanwhile, was also at Hinman’s house when he was killed and initially the details she shared about his murder and what happened at the Tate house blended together when she talked to her cellmates about killing people.

“The whole thing was done to instill fear in the establishment and cause paranoia,” Atkins told Bugliosi in an interview on Dec. 4, 1969. “Also to show the black man how to take over the white man.” In a letter to one of the cellmates she blabbed to, Ronnie Howard, she wrote, “There was a so called motive behind all this. It was to instill fear into the pigs and to bring on judgment day which is here now for all.”

But Manson, who showed up for court on day one of his murder trial with an “X” cut into his forehead (a gesture parroted by his co-defendants and many of his young female followers who clustered outside the courthouse every day), cannily tried to separate himself from the ideology.

He said on the stand: “Helter Skelter means confusion. Literally. It doesn’t mean any war with anyone. It doesn’t mean that those people are going to kill other people. It only means what it means. Helter Skelter is confusion. Confusion is coming down fast. If you don’t see the confusion coming down fast, you can call it what you wish. It’s not my conspiracy. It is not my music. I hear what it relates. It says, ‘Rise!’ It says ‘Kill!’

“Why blame it on me? I didn’t write the music. I am not the person who projected it into your social consciousness.”

Michael Rougier/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Still not a rational reaction to the White Album, but throughout Manson maintained that he was innocent of the seven murders in question.

“You start to say, ‘Well, why would they manufacture a narrative?'” Day says. Because, he explains, “they didn’t have the evidence against Manson and they had a really terrible case against him, and he might have walked.”

The narrative served to appease “a very terrified and upset public,” he continued. And, “there was an actual, legal reason for them to create this thing, because they couldn’t convict Manson, so they created a narrative that made his conduct illegal…What they actually argued was this ‘Helter Skelter’ race war [that he touted to his followers] was such that it made him vicariously responsible. His ideology made him responsible for the murders.”

Stephen Kay told Day, as relayed in Hippie Cult Leader, that he first found out about the “Helter Skelter” motive from Bugliosi’s first co-prosecutor Aaron Stovitz, when Stovitz and Bugliosi were about to go to the grand jury with it, “and to say it was an unusual motive is an understatement.” “It is weird,” Kay acknowledged, “but fortunately, there was a lot of evidence.”

When asked, Kay told Day that he didn’t think the Family wrote anything more explicitly incendiary on the walls because, in their eyes, they reasoned that the black community would just know what they were doing. At the same time, Manson supposedly envisioned, white people in general would assume that black people were responsible for the murders and the race war would commence.

“It just seems like a lot of dots to connect,” Day said, to which Kay replied, “Well, remember these weren’t ordinary people.”

O’Neill, meanwhile, writes that Stovitz told him that he never thought there was any reason for the Tate-LaBianca murders other than to get Beusoleil out of jail.

The author cites a storied recording of a phone call (which at some point fell off the face of the earth so he could only rely on others’ memories of it) made by Beausoleil from jail to Spahn Ranch. Linda Kasabian is said to have answered and Beauloseil told her that he needed help and to “leave a sign.” That night, Sharon Tate and her friends were killed.

Beausoleil, for his part, denied making the phone call.

Burton Katz, who prosecuted Beausoleil for the Hinman murder at a second trial, also told O’Neill that he thought Bugliosi mainly wanted “something sexy” to explain the Tate-LaBianca killings, or more sexy than a copycat motive, at least.

Day writes in his book that it “seems fairly apparent that Sadie’s [Atkin’s] intention was to stage the crime scene [at the Tate house] to make it look like the person who had killed Gary Hinman was still on the loose.”

At the same time it would stand to reason that Manson harbored a grudge against Terry Melcher, and wanted him dead, though Atkins told police that Watson had told her and the other girls that they were “going to a house up on the hill that used to belong to Terry Melcher, and the only reason why were going to that house was because Tex knew the outline of the house.” Asked if Watson had given a reason, she replied, “To get all of their money and to kill whoever was there.”

None of which would explain why they went out the next night to the LaBiancas, as well. The more fanatical theory almost makes more sense in the second case.

Bobby Beausoleil, who remains in prison for Hinman’s murder, told Day, “The second night at the LaBiancas was to cover up for what Charlie had inadvertently done the first night, which was to kill a house full of people. He didn’t realize it was going to be this big thing that had unfolded up there at the house on Cielo. He didn’t know that Terry Melcher had rented the place out, so it basically turned into a fiasco.”

David F Smith/AP/Shutterstock

“Charlie picked people he had grudges against,” Beausoleil also said. “He didn’t just pick people at random. That’s critical because it’s not what Bugliosi was saying—[which is] that Charlie was just sending people out to kill, willy nilly.” (The Hinman murder had to do with drugs, money and protection from the motorcycle gang the Straight Satans after Manson shot a drug dealer named Bernard Crowe in the stomach.)

And Manson had a grudge against the LaBiancas, or at least whoever was in their house, Beausoleil explained, because he and some other Family members had been living in their bus parked outside Harold True’s house, when the neighbors called the cops and they were forced to leave.

It was the family home that Leno had grown up in, but he and Rosemary didn’t move in until after True had moved out from next door.

Kay acknowledged to Day that they didn’t have evidence of Manson directly telling Watson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, Van Houten and Kasabian to go out and kill people, or to ignite “Helter Skelter,” on the nights in question. Rather, Kay said, Manson told them, “‘Go with Tex, and do what Tex tells you to do.'” That, combined with what Manson had said about “Helter Skelter” at other times, mainly according to Kasabian, put him away.

“She never asked for immunity from prosecution, but we gave it,” Bugliosi told London’s Observer in 2009. “She stood in the witness box for 17 or 18 days and never broke down, despite the incredible pressure she was under. I doubt we would have convicted Manson without her.”

To be clear, none of the aforementioned authors are Manson apologists, whatever their opposition to Bugliosi’s “Helter Skelter” theory. They don’t think he should have been walking around a free man until his death in 2017. Whether prosecutors had a beyond-a-reasonable-doubt case against him for first degree murder or not didn’t change how dangerous he was, or how insidious the ideas he unquestionably did have proved to be to his followers.

“He would readily tell you that he was this nefarious underworld character who did nefarious, underworld things,and he lived by a code outside of the law,” Day told E! News. “He was clear about that. He felt that way, he relished that depiction of himself.”

Though he claimed not to have ordered anyone else to kill, Manson was still a violent man who readily shot someone. He was still a rapist, racist and master manipulator whose actions and words resulted in people dying. As of August 2019, according to the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Police Department still has a dozen unsolved homicides on its plate officially linked to Manson, but there could be more.

“Manson—who was uneducated but highly intelligent—had this phenomenal ability to gain control over other people and get them to do terrible things,” Bugliosi, who never publicly wavered from the argument he laid out in 1970, told the Observer in 2009. “Eventually he convinced them that he was the second coming: Christ and the Devil all wrapped up in the same person.”

Dianne Lake, who was 14 when she first met Manson and participated in the new Oxygen special Manson: The Women, directed by Day, compares her devotion to Charlie half a century ago to a drug addiction.

“I have never taken heroin, but I hear people who have taken heroin, how they get addicted is they’re looking for that same incredible high they had the firs time,” she told E! News in a recent interview. “That’s how I relate sticking with Charlie and the girls, is I wanted that same feeling again that I experienced in the very beginning.”

NBCUniversal

As for actual drugs, Lake—nicknamed “Snake” in the group because she told the other girls how she had envisioned what it would be like to be a snake on a hot day, slithering through the cool grass—remembers dropping acid weekly.

“He made each one of us feel like we were super-special and his favorite,” she said of Manson, “and an integral part of his group.”

And when Tex Watson told her that he had killed someone because Charlie told him to, Lake didn’t leave. She was scared and, simply, she had nowhere to go.

Eventually Lake was called to testify for the prosecution, and when asked if she had loved Manson, she said yes.

“Then [Charlie] pipes up and says, ‘Don’t put it all on Mr. Manson, she loved everybody,'” she recalled. “That was kind of the moment I saw through his charade, his performance.”

Lake’s origin story—already emancipated at 14 from her itinerant hippie parents—was unusual in and of itself, but her susceptibility to Manson’s charms was not. Susan Atkins’ parents were alcoholics and she said that she had been molested by her brother and his friends. Patricia Krenwinkel had a hormone deficiency that made her particularly insecure about her looks and she turned to drugs and alcohol as a teenager. Van Houten started using drugs after her parents divorced when she was 14 and ran away to San Francisco, returning home pregnant to Southern California. She had an abortion and finished high school, then started secretarial school, but dropped out and went back to the Bay Area, where she met Beausoleil, who later introduced her to Manson. Tex Watson dropped out of college and was using and selling drugs by the time he met Manson.

Manson “had this uncanny ability to morph into any number of different personalities,” Lake said. “I think that he became whoever each one of us needed at the time.”

And once they all found Manson, they had a common purpose—being there for him, and each other, no matter what.

To this day, however, with dozens of books written, numerous documentaries and dramatizations filmed and the tale resurgent (and re-imagined) on the big screen right now in Quentin Tarantino‘s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the thread tying all of it together is still loose in places. Connections remain missing amid the dots.

Even Bugliosi didn’t claim in Helter Skelter to have all the answers.

“All of these factors contributed to Manson’s control over others,” he wrote (with co-author Curt Gentry), detailing the vulnerabilities of Manson’s followers and the ways he both controlled and conned them. “But when you add them all up, do they equal murder without remorse? Maybe, but I tend to think that there is something more, some missing link that enabled him to so rape and bastardize the minds of his followers that they would go against the most ingrained of all commandments. Thou shalt not kill, and willingly, even eagerly, murder at his command.”

No matter why they did what they did, no one has been able to fully explain that part of it, how Tex, Katie, Sadie and Lulu—all troubled, yes, but with no pre-Manson history of violence—turned into butchers.

“What’s real has different levels,” Manson, a shrewd teller of tales to the end, told Day. “You could go on certain levels of reality that other people don’t really understand at all. So, they call it insanity.”

Or as O’Neill wrote in Chaos, “I’ve learned to accept the ambiguity.”

Be the first to comment