Since her heartbreaking, premature death in 2012, Whitney Houston‘s life has been examined from every angle.

In those first days after she was discovered face down in a hotel bathroom seven years ago, on Feb. 11, 2012, countless obituaries were written, reflecting on the legacy of the 48-year-old musical icon, her brilliant, unmatched voice and the enumerable hardships she faced.

Then came the postmortem discoveries: Former husband Bobby Brown claimed in an interview “both of us cheated on each other,” and said in his 2016 memoir, Every Little Step, that they had tasked a nanny to care for daughter Bobbi Kristina Brown in another wing of the house while they got high. And the 2017 documentary Whitney: Can I Be Me alleged a bodyguard was fired after filing a detailed report of the singer’s drug use.

And, of course, there was a new rush of articles in 2015 when, in an eerie twist, Whitney’s only child, then-21-year-old Bobbi Kristina was found unresponsive in much the same state as her mom, passing away six months later without ever regaining consciousness.

Then came Whitney. The 2018 documentary, painstakingly assembled with the help of Houston’s relatives and closest companions, revealed even more agonizing truths about the seven-time Grammy winner’s life. As a child, her half-brother Gary Garland-Houston and assistant Mary Jones allege in the film, Whitney was sexually molested by her cousin, singer Dee Dee Warick, sister of music legend Dionne Warwick. The traumatizing incidents, Jones suggests, would lead Whitney to question her sexuality for the rest of her though she went on to marry R&B bad boy Brown in 1992.

Mom Cissy Houston remains torn on the validity of the accusation, noting in a statement to People, that neither Whitney nor Dee Dee are alive to “deny, refute or affirm” the accusations. But Jones felt it important to share. She “decided this was the elephant in the room that nobody wanted to talk about,” director Kevin Macdonald explained to IndieWire of the sexual abuse ahead of the film’s premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. “And she felt so strongly that this was the thing that was the catalyst of so many things in Whitney’s life. She wanted to talk about it.”

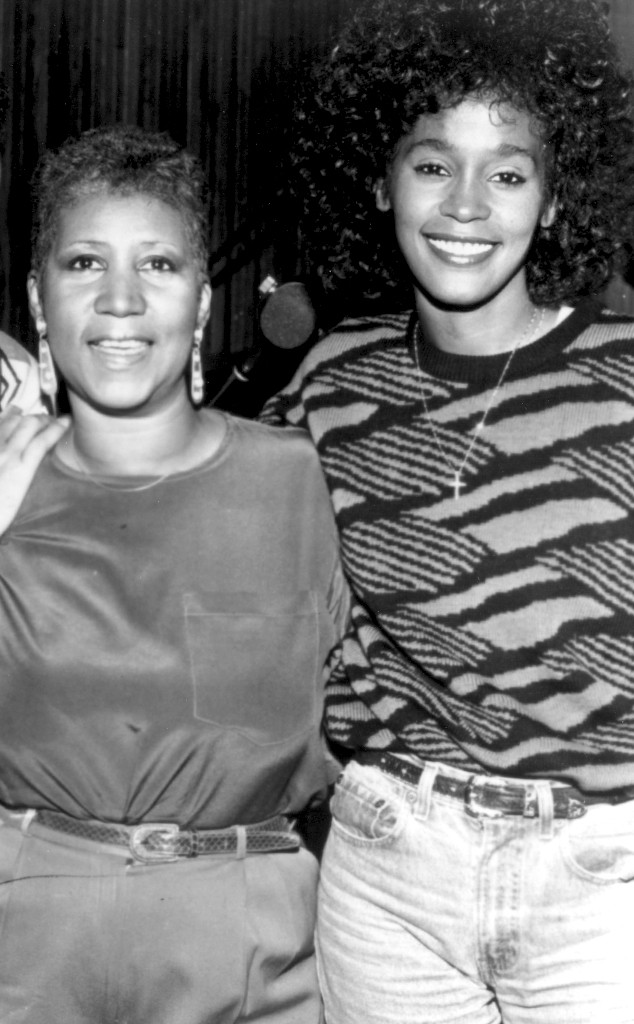

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Now there’s another confidante with a story to share. For years, Robyn Crawford was solely described as Houston’s pal and assistant-turned-creative director. But, as Crawford shares in her just-released memoir A Song For You: My Life With Whitney Houston, they were so, so much more.

“We were intimate on many levels and all I can say was that it was very deep and we were very connected,” Crawford shared in a recent sit-down with Craig Melvin for Today and Dateline. “Our friendship was a deep friendship. In the early part of that friendship, it was physical.”

As she wrote of their initial encounters back in 1980, “We wanted to be together and it was just us. The physical part of our friendship happened along the way and it was just as beautiful. We were on a journey together and we were connected.”

Houston’s journey, as backing vocalist Pattie Howard put it, Whitney began in “the ‘hood” of Newark, N.J. But after the 1967 race riots, her family settled in nearby, middle class East Orange. The daughter of gospel and pop singer Cissy (she backed up Elvis Presley and Aretha Franklin, who would become Whitney’s godmother) and cousin of Dionne Warwick, she had the skills, beauty and pedigree to become a pop star.

Ron Galella, Ltd./WireImage

She cut her teeth singing in the choir at Newark’s New Hope Baptist Church, before trying her hand at modeling (she would appear in the pages of Seventeen, Glamour and Cosmopolitan) and working as a backup studio singer for the likes of Chaka Khan and The Neville Brothers. Though talent scouts expressed interest in backing her career, Cissy insisted they would have to wait until the teen graduated from her all-girls Catholic high school.

That big break would come when Gerry Griffith, director of A&R for Arista Records heard the 18-year-old deliver a solo at New York City’s Seventh Avenue South nightclub. He signed her and tasked none other than label founder Clive Davis with supervising the two-year production of her self-titled 1985 debut—a disc that paired her three-octave, impassioned vocals with polished, catchy tracks such as “Saving All My Love for You,” “How Will I Know” and “The Greatest Love of All”.

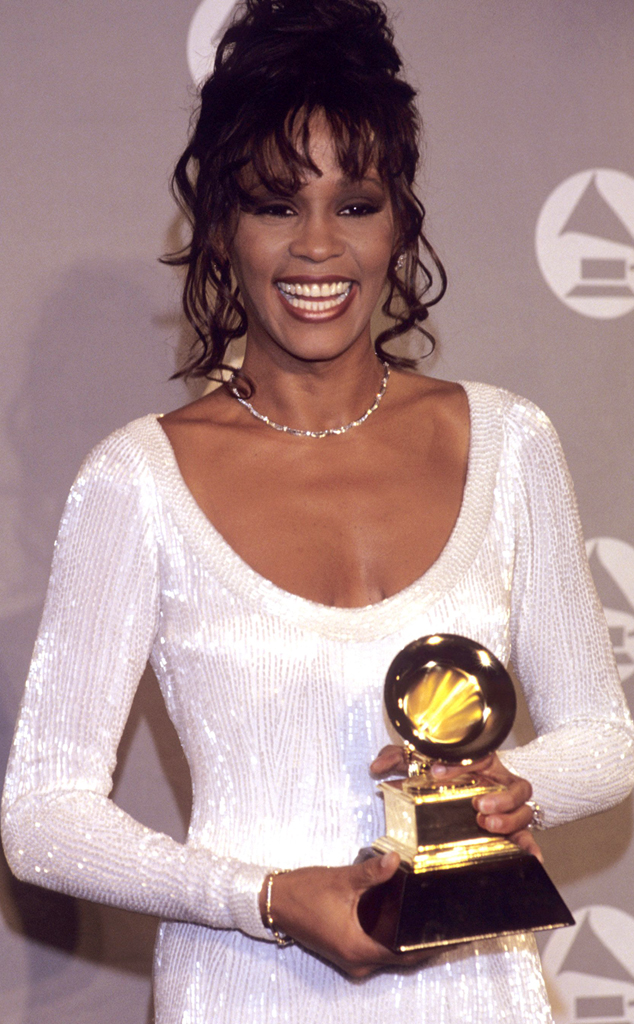

The trio of number one singles and a best female pop vocal Grammy, matched with her good girl image propelled Houston away from her humble roots into the upper most echelon: celebrity. Her follow-up, 1987’s Whitney notched four more hit singles while the slightly more R&B-laced I’m Your Baby Tonight, brought in two more in 1990.

Larry Busacca/WireImage

But her carefully cultivated persona and success (her seven consecutive number one hits pushed her past The Beatles’ previously held record) presented drawbacks. At the height of her career, Whitney was roundly booed at the 1989 Soul Train Awards—the popular assumption being that black audiences disapproved of her crossover style. In Cissy’s 2013 memoir, Remembering Whitney she recalled hearing someone “yelling ‘White-ey! White-ey!’ like it was something clever.”

Whitney would muse to Ebony in 1991 that fans “had just gotten sick of me and just didn’t want me to win another award,” but in a chat with Arsenio Hall that same year she agreed that race had played a role.

“They boo me at the Soul Train Awards…I don’t really know what it’s about. But I think that I’ve got a lot of flak about I sing too white or I sing…white or something like that. I think that maybe that’s where it comes from,” she told Hall. “I haven’t had the opportunity to ask why I get booed at the Soul Train Awards, but I grew up on Soul Train just like every other black kid, you know?…I do sing the way God intended for me to sing and I’m using what he gave me and I’m using it to the best of my ability.”

Her sound wasn’t her only strife. Houston was also allegedly hiding her romance with Crawford. An all-state basketball star two years her elder, Crawford met Whitney when the singer was just a 16-year-old summer camp counselor, but she already had big visions for the future. “She looked like an angel,” Crawford recalled in an Esquire tribute the day after Whitney’s death. “Not long after I met her, she said, ‘Stick with me, and I’ll take you around the world.’ She always knew where she was headed.”

It was at Houston’s home that summer the pair shared their first kiss, Crawford wrote: “We talked and talked. And then all of a sudden, we were face to face. The first kiss was long and slow, like honey. As we eased out of it, my nerves shot up and my heart beat furiously. Something was happening between us.” Their intimacy deepened, Crawford described, not long after at a friend’s apartment: “We took off our clothes, and for the first time, we touched each other. Caressing her and loving her felt like a dream.”

When Whitney moved out of the family home at 18, the women roomed in an apartment together.

“I don’t think she was gay, I think she was bisexual,” Whitney’s make-up artist and friend Ellin Lavar noted in Whitney: Can I Be Me. “Robyn provided a safe place for her. In that, Whitney found safety and solace.”

But not the freedom to come clean about her romance. Crawford recounts in her book that Whitney informed her they could no longer be together shortly after she signed her record deal in 1982. “She said we shouldn’t be physical anymore because it would make our journey even more difficult,” the fitness trainer wrote. “She said if people find out about us, they would use this against us, and back in the ’80s that’s how it felt.”

Crawford gracefully accepted the decision—”I just felt I wouldn’t be losing much,” she explained on Today. “I still loved her the same and she loved me and that was good enough,”—but Brown told Us Weekly he believed “Whitney would still be alive today” if Crawford had been accepted into her life. Instead, he said, the singer felt the need to keep their bond hidden, fearing Cissy’s disapproval.

Al Messerschmidt/Getty Images

She was right to worry. In her 2013 book, the matriarch wrote about her dislike for Crawford, a woman she thought spoke too much and acted overly familiar. Her words caused Oprah Winfrey to ask her in an interview that same year, “Would it have bothered you if your daughter was gay?” “Absolutely,” Cissy answered. Would she have condoned it? “Not at all.”

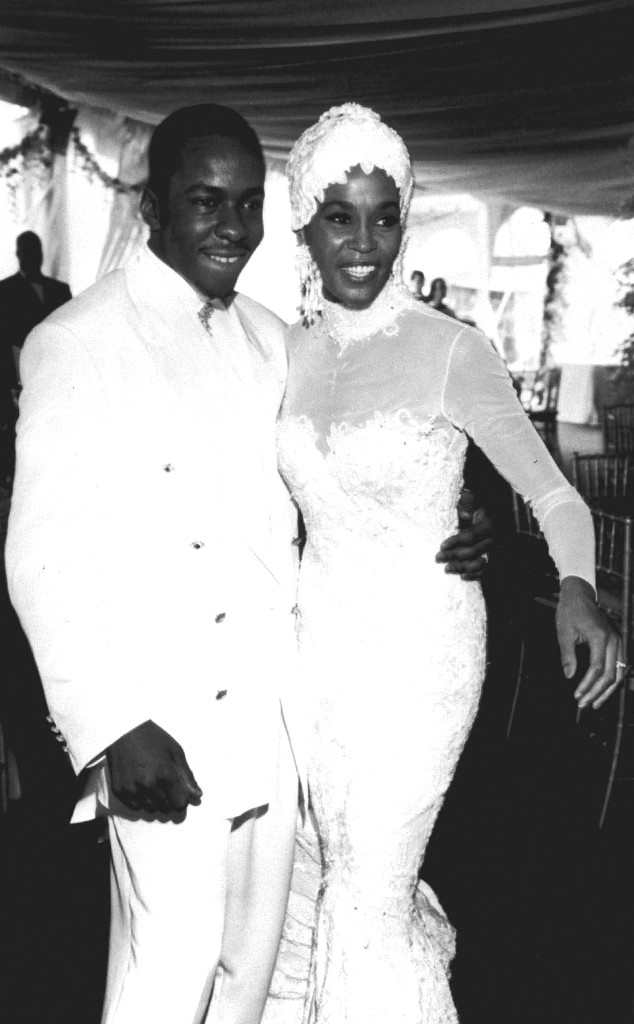

So when Houston crossed paths with Brown at that same fateful Soul Train Awards, the New Edition bad boy (at 20 he’d already been shot at and stabbed and fathered two kids) seemed the perfect solution to both of her problems and the instantly smitten singer reportedly declared, “That is going to be my husband.” They wed in front of 800 guests at her New Jersey mansion in July 1992 and welcomed Bobbi Kristina eight months later.

“This was a choice of hers of someone that she said she loved and wanted to spend the rest of her life with,” Crawford told Today.

Together, they were a formidable pair. Brown gave Houston the street cred she so desperately desired as she continued to churn out pop hits and venture into acting, with her first memorable role as a pop diva in 1992’s The Bodyguard. (Thanks, in large part, to her stunning version of Dolly Parton‘s “I Will Always Love You,” the film would produce the best-selling soundtrack of all time.)

Associated Press

But their union was an uneasy one. In Derrick Handspike’s unauthorized biography Bobby Brown: The Truth, The Whole Truth and Nothing But… he quotes Brown as saying, “Now I realize Whitney had a different agenda than I did when we get married. I believe her agenda was to clean up her image while mine was to be loved and have children. Whitney felt she had to make rumors of a lesbian affair go away. Since she was American Sweetheart and all, that didn’t go too well with her image. In Whitney’s situation the only solution was to get married and have kids. That would kill all speculation whether it was true or not.”

And then, of course, there were the drugs. It’s easy to suggest Brown set the church-going gospel singer on the pathway to her addiction. But that dubious honor actually belongs to her older brother Michael Houston, who admits in Whitney that they first started getting high together when she was 16.

Ron Wolfson//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Brown, himself, claimed in his 2016 memoir, Every Little Step, to not have even been aware of Whitney’s drug use until he saw her “hunched over a bureau snorting a line of coke” moments before they were to walk down the aisle.

It was a scenario brother Michael simply hadn’t envisioned when they were teens. “We were always, you know, being together most of the time, and her following behind me—I taught her to drive,” he explained to in a 2013 interview with Winfrey. “We played together—everything that you do together as you’re growing up—and then when you get into drugs, you do that together too and it just got out of hand.”

To put it mildly. In her own interview with Winfrey, years before her death, Whitney would confess to lacing joints with cocaine and spending days and nights watching TV and getting high with Brown, at one point not changing out of her pajamas for some seven months. By the mid-00s, according to the documentary Whitney, the couple had set up a make-shift craft den in the bathroom of their Atlanta Home—right around the time Whitney was famously declaring to Diane Sawyer that “crack is whack.”

It was her most memorable line, to be sure, but perhaps not her most troubling. In a 2000 Jane profile (she showed up four hours late to the accompanying photo shoot), she was asked the difference between spending time with a president (by that point she’d met both George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton) and a junkie. Her response: “Just the same. The president gets off on the country. The junkie gets off on a couple of hits.” The next year, after she canceled an appearance at a Michael Jackson event, rumors surfaced that she had overdosed and died.

While Brown was often labeled as the instigator in the star’s downfall, Whitney: Can I Be Me director Nick Broomfield sees it differently. “It’s not like Bobby is a bad person,” he explained in an interview with Irish Times. “It’s just that Bobby and Whitney were unable to support each other, constructively. Instead, they enabled each other. They were totally besotted with each other. But they were unable to support each other in order to change. I think their close friends saw that. Bobby wasn’t a terrible person. Whitney wasn’t a terrible person. They just couldn’t change while they were together. That’s why they had to end.”

ABC/CRAIG SJODIN

By the time Whitney finally filed for divorce in September 2006, she had already endured two stints in rehab, Brown’s 2003 arrest for domestic violence and one season of their equal parts memorable and disturbing reality show, Being Bobby Brown.

But while she had escaped her toxic marriage, after years of drug use she’d once categorized as “heavy” her most powerful weapon, her voice, wasn’t the same. The shift was noticeable at a 2009 Good Morning America performance in NYC’s Central Park and in the mixed reviews of her “Nothing but Love” tour that followed, both supporting what would be her final album, I Look to You, released 10 years ago.

By then, loved one were already fearing the worst. As make-up artist Lavar said in Whitney: Can I Be Me, “For 10 years or so I started waiting for the phone call that we all eventually got.”

When it came through, Whitney had been making a play at a comeback. She had just wrapped work on her role in the Sparkle remake, playing the mom to American Idol champ Jordin Sparks, and on the evening of Feb. 7, 2012 she had shown up—on time—to the studio to record her side of their duet, “Celebrate.”

As producer Harvey Mason Jr. noted to Vanity Fair, “She was way more energetic than the young people, more excited to be in the studio, more passionate to make something outstanding.”

Four days later, she woke up in her presidential junior suite at The Beverly Hilton, the site of Davis’ annual pre-Grammy shindig where she was set to perform.

Her assistant, Mary Jones, laid a dress out on the bed, then stepped out to pick up a second option from Neiman Marcus. When she returned, shortly after 3:30 p.m., Houston was facedown in the bathtub. Paramedics were called, CPR was administered, but to no avail. The singer’s death would later be attributed to accidental drowning, heart disease and cocaine use. An open bottle of champagne and a spoon containing what the coroner’s report called a “white crystal like substance” were spotted at the scene and traces of a muscle relaxant, Xanax, Benadryl and marijuana were found in her system.

Downstairs, as distraught luminaries such as Tony Bennett, Diana Ross, Britney Spearsand Mary J. Blige arrived, the party commenced, the superstar’s loved ones insisting they celebrate. “Simply put, Whitney would have wanted the music to go on,” Davis told partygoers, “and her family asked that we carry on.”

While Whitney has taken her final bow, her greatest legacy—that ability to entertain, that propensity to stun crowds, that voice—continues.

“I, like every singer, always wanted to be just like her,” Beyoncé stated after Houston died. “Her voice was perfect. Strong but soothing. Soulful and classic. Her vibrato, her cadence, her control. So many of my life’s memories are attached to a Whitney Houston song. She is our queen and she opened doors and provided a blueprint for all of us.”

And for all her flaws there’s something innately endearing about the person Whitney was—beyond the music. “She had a huge story,” sister-in-law Pat Houston tells E! News, adding that the 2018 documentary is their way of putting the mistakes to rest so they can celebrate her life.

“Everybody loved her,” Cissy echoes in Whitney. “She was a little girl wishing upon a star, always trying to find her way back home.”

(This story was originally published on February 11, 2019 at 6 a.m. PT.)

Be the first to comment