The history of the Met Gala can be divided into three eras: Eleanor Lambert‘s founding, the Diana Vreeland renaissance and the Anna Wintourempire.

Without these style icons, the Met Gala would merely be a fundraiser rather than the party of the year. One could even say that without these trailblazers, fashion wouldn’t be included among the works of art that are currently displayed for the masses at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Instead, these timeless pieces would remain in the vaults of famous ateliers, collecting dust.

But Eleanor Lambert, among others, had a different vision for the ensembles designed by Christian Dior, Coco Chanel and designers across the world. As a fashion publicist, who founded the Council of Fashion Designers of America and New York Fashion Week, Eleanor believed that, contrary to popular belief, clothes and other garments hold as much value as the next Picasso or Michelangelo, thus earning a place among other historic items.

Of course, convincing the intellectuals of this idea took effort and a whole lot of money.

But having earned her spot among the elites in New York had its advantages. For one, Lambert had access to the people with deep pockets. Secondly, her experience as a publicist gave her the know-how for garnering attention for a great cause.

With these two things in mind, invitations were sent out to New York’s upper echelon and higher-ups from the fashion industry in 1948, welcoming them to an elegant dinner and reminding them to bring their checkbooks—they would need it.

In the early years, the dinner cost $50 to attend, equivalent to $550 in 2020, and was hosted at New York City hotspots like the Rainbow Room, Central Park or the Waldorf Astoria. It was a quaint, intimate soiree for the elite of the elite that would keep the Costume Institute afloat for the years to come.

And though Lambert’s dinner marked the opening of a new exhibit, as tradition dictates, themes weren’t introduced until Vogue‘s former editor Diana Vreeland came into the picture in 1972.

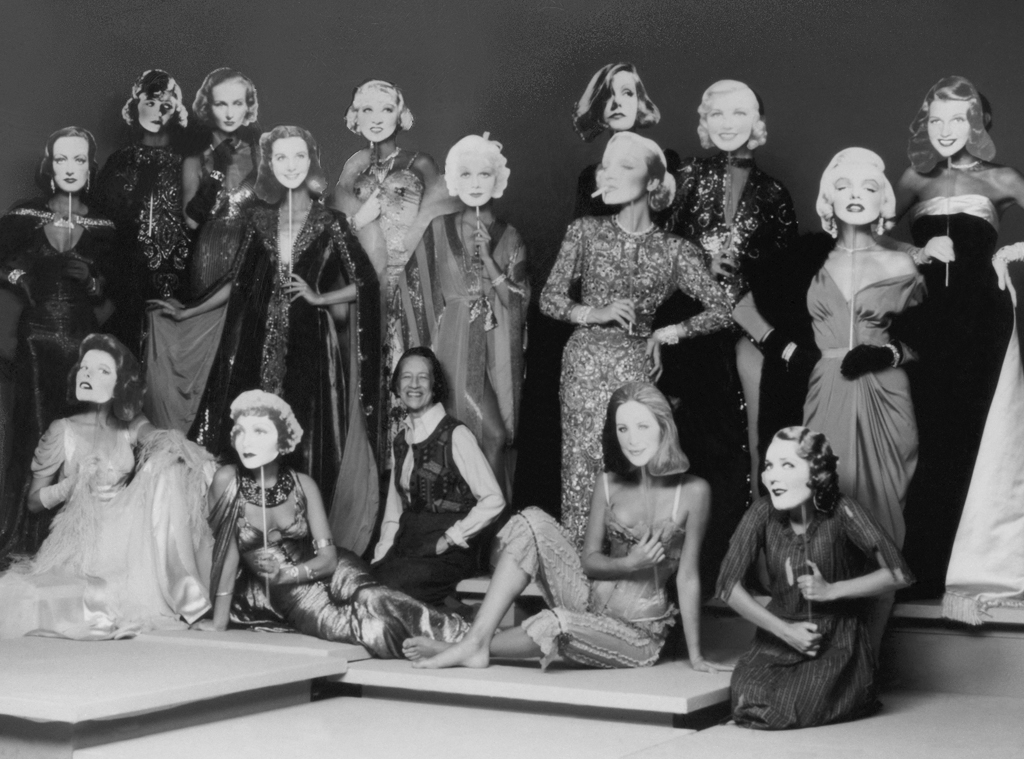

Francesco Scavullo/Condé Nast via Getty Images

Fresh off her role as Editor-in-Chief of Vogue, Vreeland was seeking a new position to fuel her lust for creativity and all-around extravagance. Her A-list entourage, which included Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, knew of such desires and are rumored to have “raised enough money to fund her salary for the first two years,” according to Architectural Digest.

With a salary financed, Diana was brought on as a consultant for the Costume Institute in 1972, thus bringing about a flurry of changes that altered the course of history. Gone were the drab dinners in the Waldorf Astoria and in its place were grandiose themed parties in the Met.

From that point on, the event would be recognized as the Met Ball, a name more fitting for a gathering of its stature. Although, informally it was dubbed the “Party of the Year” or the “Oscars of the East Coast,” due to the rapidly growing guest list filled with entertainers, politicians and actors.

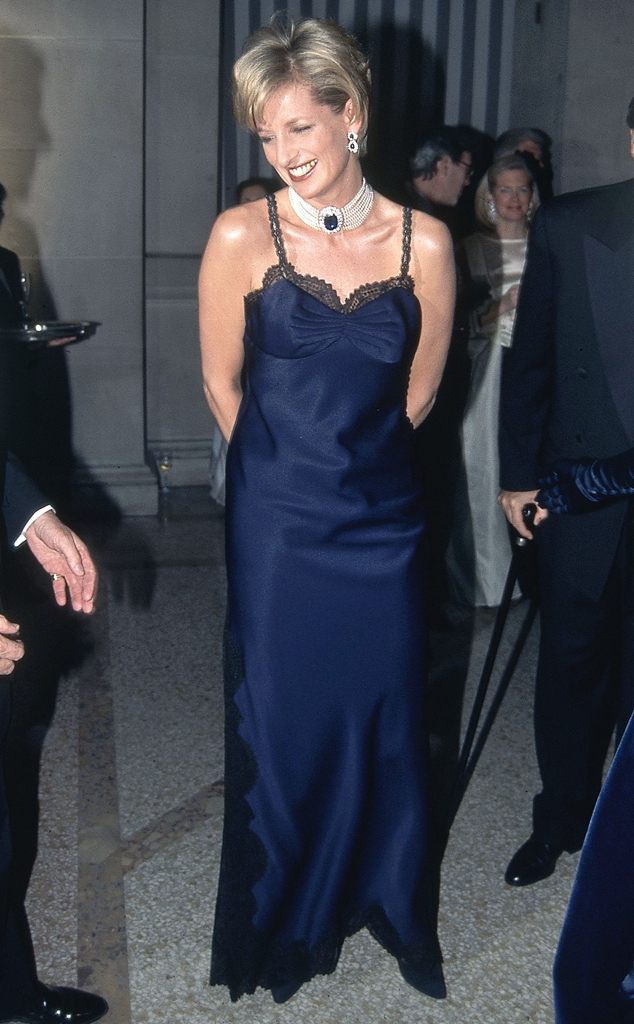

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

Unlike her predecessor, Vreeland was open to entertaining all guests, even if they weren’t considered New York’s elite. It made no difference to her if Bianca Jagger and Diana Rosswere mixing and mingling with politicians or socialites. Vreeland was more concerned with the small details, like the odor of the Met basement.

According to New York magazine, she once requested the scent of Opium be pumped into the room for a 1980 exhibit about China. On another occasion, she had Chanel Cuir de Russie spritzed about.

Such demands were unconventional for the time, but as one museum official told The New York Times Magazine in 1981, “Forget her lack of integrity to a period; she gives visibility to the Costume Institute no money could buy.”

Diana acknowledged in the same piece that she was “difficult” to work with, but she wouldn’t settle for anything less than beautiful. Like the 18th century women she adored, Vreeland believed, “Giving pleasure and being attractive was a duty.”

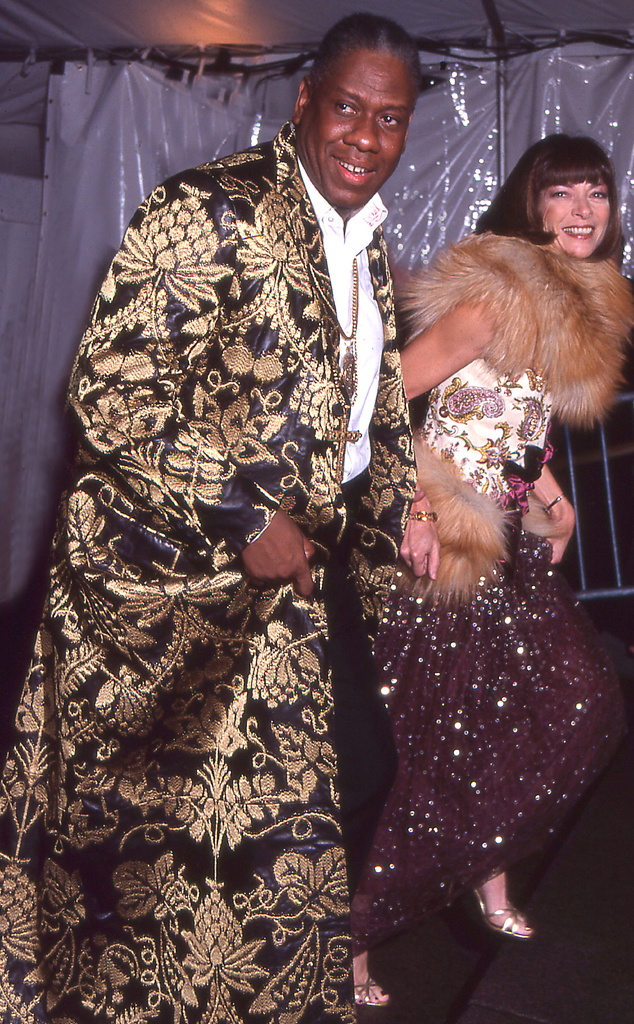

Patrick McMullan/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

She continued to uphold these beliefs until the end of her life in 1989. Her final exhibit was The Age of Napoleon, although many say the Vreeland Years ended in 1994, a year before Anna Wintour would come in guns ablazing.

By 1995, the relationship between Vogue and the Met was firmly cemented, so it only made sense for the latest Editor-in-Chief to assume the role of chairwoman. By 2005, the Met Gala wasn’t just “the party of the year,” it was “Anna Wintour’s party of the year.“

Aesthetically, the editor changed nothing. The Met Ball was still as grand and over-the-top as Diana Vreeland had imagined it. What Anna Wintour brought, however, was an air of sophistication and exclusivity. Diana might’ve welcomed the star power, but Anna did so much more.

In the 2005 documentary, First Monday in May, it was revealed that Anna’s influence went beyond seating arrangement. Though the documentary largely focused on the exhibit, Wintour was seen deciding which celebrities that each designer or brand would be allowed to invite, thus determining the appearance of the stars.

Rose Hartman/Getty Images

As a Hollywood Reporter source previously explained, “Vogue brings the designers’ clothes up to the magazine. They lay it all out and then they pair celebrities with the designers and their gowns. The level of control is amazing. The invasion of Baghdad was nothing compared to this. If Michael Kors is coming, Anna is deciding which celebrity will wear Michael Kors and which Michael Kors outfit the celebrity will wear.”

She and the Met team took it a step further when they stated on their 2014 invitations that “gentlemen are to be dressed in white tie” while women would be dressed in evening gowns. Additionally, they implemented a strict social media ban in 2015—although the celebs found a loophole in this by taking a now-historic selfie in the museum bathroom.

Though they never gave a reason for this request, one can surmise it’s because Anna found it necessary. In 2005, she told New York magazine that she felt the ball had “lost its glamour.”

And while it’s not strictly required to adhere to the theme, it’s expected that attendees dress in appropriate fashion.

Such rules, spoken or otherwise, are what helped to elevate this gala and charity to a whole new level, not only in terms of popularity but in its ability to raise money. 2019 was a record-breaking year for the Costume Institute as the Notes on Camp ball raised $15 million.

In the future, planning the Met Gala will prove to be a challenge, as Wintour and her team try to top that of the years previous. But with the coronavirus leading to the 2020 Gala being postponed indefinitely, it seems the fashion world will have to patiently wait to see what magic they can pull off for the About Time exhibit.

Be the first to comment